He Knew He Was Right

By Mark Blake

Q - July 2012

Rock's great curmudgeon once described himself as a "pretty unpleasant guy to be around." After 36 years in a career that has informed everyone from The Strokes to The Rolling Stones, he welcomes Mark Blake into his Hollywood studio and declares a long battle against record labels and celebrity vindicated. He'll also explain the origin of that scar on his left hand. "I had a bad temper," admits Tom Petty.

In conversation Tom Petty often grips his right wrist with his left hand. If you get up close you might see the trace of a scar running across the back of the band. That's the one he smashed into a wall after losing his temper one night in 1985. Doctors stuck metal pins into the broken bones and Petty spent nine months relearning how to use his fingers. He can walk through an airport metal detector without setting the alarm off, but since hitting 60, the old injury has been playing up.

"I didn't notice it for the longest time," he murmurs, "but in the last year it's started to hurt. I guess that's just down to getting old." Petty pauses to light his third cigarette of the hour. Or his fourth if you include the electronic one with the LED tip which he "smoked" while talking about the time a deranged fan burnt down his house.

In a 36-year recording career Tom Petty has played many roles: self-harmer, arson victim, punk cheerleader, corporate rock star. Nowadays he might seem cosily settled as an elder statesman of US singer-songwriters. But nothing about Petty is ever that cosy. The man who once described himself as a "pretty unpleasant guy to be around" has been railing at greedy record companies and vacuous celebrity culture longer than most. "And look around you now," he says. "I was proved right."

In June, Petty and his group The Heartbreakers begin their first European tour in 20 years. The band's musical stock keeps rising. In 2001, The Strokes reconfigured their 1977 hit American Girl for their own Last Nite ("They admit it and good luck to 'em"). These days, you can hear Petty's music floating around the background in the Foo Fighters, Jack White, folkies such as M Ward and Conor Oberst and fellow ornery Southern gentlemen Kings Of Leon. A few years ago, even The Rolling Stones thought they'd ripped him off.

"I got sent a track with a note from Mick Jagger," Petty recalls. "Mick said, I think we've accidentally taken something from one of your songs. I played the tape and I don't know what he was thinking because it didn't sound like one of mine. But, hey, everybody borrows something from someone."

Thomas Earl Petty was born in October 1950 in Gainesville, Florida. In 1961, Elvis Presley came to nearby Marion County to shoot his new film, Follow That Dream. Petty's uncle worked in the movie business and took 10-year-old Tom to the set. "Elvis was the best-looking person I ever saw," he recalls. "Girls were going crazy. So when I went out I made it my business to find some Elvis Presley records." It was the beginning of his musical obsession.

After The Beatles appeared on US TV in 1964, Petty begged his parents for an electric guitar. His father was a sports fan, fisherman and hunter; everything his artistic son wasn't. "But it was my dad who ponied up the $35 to buy me my first guitar." Petty started playing in a school group that eventually evolved into Mudcrutch, the forerunners of The Heartbreakers. He also began growing his hair, "which made me a freak around town." There was physical abuse from Petty, Sr; the root, Tom believes, of his own fiery temperament: "My dad got real pissed I wasn't more like him."

Petty's father owned the only grocery store in the black neighbourhood, but it was still the era of racial segregation. "My parents taught us to respect everyone," he insists. "But I couldn't say they weren't racist. When I was eight my mom gave me this whole rap about how black people had their own movie theatres and bathrooms, and when I asked why, she said, They prefer it that way. And I thought, I'm not buying that." Meanwhile the long hair and parental violence compounded Petty's sense of alienation: "When the Civil Rights movement came along, we knew what side we were on."

For Petty, music became everything. He skipped his graduation to play a gig, and in 1970 Mudcrutch moved to California, splitting five years later without having had a hit. Lead singer Petty was offered a solo deal. He formed The Heartbreakers in 1976 with drummer Stan Lynch, bassist Ron Blair and Mudcrutch's guitarist Mike Campbell and keyboard player Benmont Tench. "I became bandleader by accident. I didn't want the job," he laughs. "Hell, I still don't want the job."

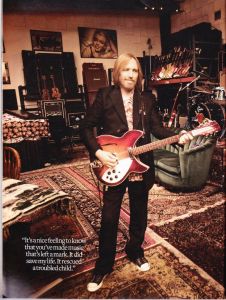

The Heartbreakers' rehearsal room/HQ can be found at the end of a dead-end street in the Van Nuys district of Los Angeles. The walls are covered by racks of guitars and hung with photographs of The Clash and Marilyn Monroe. In the doorway stands a ceiling-high totem pole, a stage prop from their 1989 tour. On the drum riser directly behind Petty's mic stand is a cigarette lighter. Everything is geared up for his arrival.

Today Tom Petty slips quietly into the room. The straw-coloured hair and beard show few signs of retreat. He's dressed in a washed-out shirt, jeans and unlaced trainers. When he shakes hands he bows his head to one side in a curiously deferential gesture. His sunglasses remain on at all times. Petty's accent is the Deep South-meets-the West Coast; his vernacular includes a little English slang. It's strange to hear Tom Petty describe having his picture taken as making him feel "like a twat."

Britain took to The Heartbreakers before America. Their 1976 debut album went Top 30 in the UK and they made their inaugural visit a year later, met at Heathrow Airport by NME journalists who thought they were rock's great white hope. The Heartbreakers played snarky tough-guy pop and were the antitheses of windy prog or glam-rock.

"Music had gotten real blown-up and corporate," recalls Petty. "We wanted to get things back on the right path. God Save The Queen had come out. We felt a kinship to the punk thing, and were embraced by those bands. I remember some of the Sex Pistols came out to see us."

Before long, America had caught on. Tom Petty And The Heartbreakers' third album, 1979's Damn The Torpedoes, with its belligerent-sounding anthem Refugee, sold two million copies. Now the blond-haired, whippet-thin singer with the permanently vexed attitude was fast-tracked to stardom: booze, cocaine, a big house in Encino, California: "That's when things started to get a little crazy," he says. "I had to have security guards at my home, which isn't a good way to live."

That the Heartbreakers' next album, 1981's Hard Promises, included a song called Nightwatchman all about Petty's bodyguard, showed how much his life had changed. But the album nearly didn't come out. MCA wanted to roadtest a new "superstar price" tag of $9.98 (a dollar more than a regular album). Petty risked career suicide and refused to deliver until they relented. But the stand-off showed him who his friends were: "I kinda hoped someone else would step up but nobody did. No other musician. Not one."

You sense that this resentment has never left him. It's alway been Tom Petty Vs The Rest Of The World. By now the former punk sympathiser was part of the establishment: "I liked punk but I wasn't gonna spike my hair up and pretend to be something I wasn't." His critics, especially in the UK, now viewed him as another corn-fed American rocker in the Springsteen tradition. "I never thought Bruce and I were doing the same thing," he says defensively. "I wasn't trying to do The Great American Novel." But, like Springsteen, Petty saw in the '80s as a platinum-selling artist who sung about cars and girls.

It was his desire to mess with the formula that led him to make 1985's Southern Accents. Petty wanted to make a concept album that reconnected with his roots. It didn't quite turn out that way. One night, blurry with drugs and alcohol, he was so upset by a song mix that he punched a wall, shattering the bones in his left hand: "I did a stupid thing that night and I paid dearly for it." Lying in hospital he watched an MTV news report claiming he would never play guitar again.

"I had a bad temper," he sighs, reaching for the electronic cigarette. "I had a temper that could just flare up and take over. And I would stay mad for a long time." If breaking his hand was a wake-up call, it took Petty longer to regain full consciousness. Southern Accents, with its spooked-sounding hit single Don't Come Around Here No More, was another success. But Petty took a cameo role in a dire fantasy film Made In Heaven, left his wife Jane and their two daughters and holed up in LA's Sunset Marquis hotel for a month. "A strange time," he smiles thinly. "I discovered that this is a hard racket to stay married and raise kids in." Then in May 1987, an arsonist burned his house down.

"The police discovered this mad somebody had been staking the place out," he winces. "He'd cut a hole in the fence and was on a hill behind the house just watching." Nobody was hurt, but the family lost almost everything. Petty drove back one night after rehearsal, forgetting what had happened. He was parked in his driveway before realising his home was now a burnt-out shell. "I came away with the realisation that stuff is temporary. It can be replaced. We found a new house and stashed the family...and I took off on the road with Bob Dylan. I was traumatised but I didn't deal with it for a long time."

In the end, he put himself into therapy. "It's hard when you're young and you don't want to talk about personal things. But through therapy..." He pauses and laughs, conscious of slipping into "therapy-speak," "...I learned that my anger was a result of being beaten frequently. So I worked it out. I'm not angry any more."

On his 1987 hit, Jammin' Me, Petty spat venom at overexposed celebrities. But he would never sound so cross again. Instead, he put the Heartbreakers on ice and ran off with Bob Dylan to form The Traveling Wilburys, a superstar love-in that also included George Harrison. Petty, the Beatle fanboy, was now playing with his idol. "At the beginning I was dumbstruck," he admits. "Then on the third day, George turned round and said to Bob, Of course, you're Bob Dylan, but is it OK to treat you like anyone else? We were all in awe of each other."

Tom Petty spent the rest of the decade as "just one of the band" in The Traveling Wilburys. Then his 1989 solo album Full Moon Fever became his biggest US and UK hit since Damn The Torpedoes, souring relationships inside the Heartbreakers boys' club. "There was resentment," he nods, offering another thin smile. "But they got over it."

Ever since, Petty has drifted easily between group projects and solo records. The graceful Wildflowers (1994) was a Top 10 hit and became a set text for the alt-country generation. But with his marriage over, Petty went to live alone in a remote shack in the Pacific Palisades, just outside LA. Was it a breakdown? "No, but I didn't want to leave while my kids were still young," he says carefully. "I had to be completely alone. The career was on the up, but I had to readjust to life. I wasn't happy."

It was his second wife, Dana, whom he met at once of his concerts, who helped bring him out of himself again: "She'd had a divorce as well, so we were both real cautious." In the meantime, musicians who'd grown up with Tom Petty on the radio had appeared on his radar: "I thought Kurt Cobain was the last Beatle-type figure to come into rock'n'roll. I thought he was amazing." When Cobain died, Dave Grohl considered replacing the Heartbreakers' departed drummer Stan Lynch. He played a Saturday Night Live show with the band: "But I'm not sure he'd have been happy hanging out with such old guys. Then he told me he had done his own album called the Foo Fighters...I said, You're never gonna be happy with me if you leave that."

Petty rediscovered some of his bile on 2002's The last DJ, where he fulminated at the moral bankruptcy of the music industry. Radio stations thought they were the target and refused to play the title track: "It was misunderstood and I felt disheartened. But look what I was saying about the industry all those years ago. I knew I was right." There's a triumphant smile; suggesting pleasure taken in poking a stick at the music business and pride in his clairvoyant abilities.

As The Heartbreakers' most recent album, 2010's cranky blues-rock set Mojo, demonstrates, Petty's inspiration now comes exclusively from the past. "Jack White has the right idea," he says. "I like musicians with roots, people that are grounded in something. But for me, it's all about finding where shit comes from and working my way back." Sometimes that even includes his own "shit."

"Dana plays my stuff. We'll be in the car and she'll make me listen to an album I've not heard since I made it. It's nice because sometimes I'm damned if I can remember what track comes next." He stands up, bows his head to the side and offers his good hand. "It's a nice feeling to know you've made music that's left a mark. It did save my life. It rescued a troubled child. I owe it a great deal." And with that, he strolls off towards the drum riser and picks up his cigarette lighter.