American Boy

By Alan di Perna

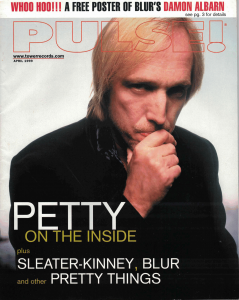

Pulse! - April 1999

Pop's understated populist Tom Petty on ambivalence, authenticity, Elvis, and Echo

Tom Petty's body language has the same spare economy as his song lyrics. He's not a man to waste words, or energy. Crossing a room, he seems to arrive at his destination with the least possible amount of effort, more of a glide than a walk. He dissolves onto a '50s Moderne sofa in L.A. photo studio, surrendering his compact frame to the couch's parabolic contours. It would be unfair to say that Tom Petty is lethargic. There's something more deliberate than lethargy in his laid-back personal style, as if some subconscious part of his brain is continually calculating the path of least resistance. Lethargy would mean a sacrifice of momentum. And that wouldn't do at all.

Petty's come down to L.A. from his home near the sunny Malibu coastline to discuss his new Warner Bros. album with the Heartbreakers. Titled Echo, the disc is something of a departure for Tom and the boys. Not so much musically; the band's jangly, incisive roots rocks instincts are as sharp as ever. But a darker lyrical mood hangs over much of the new opus. The songs are tinged with a sense of regret, loneliness and vulnerability. "You need rhino skin, if you're gonna pretend you're not hurt by this world," Petty sings at one point. It's a funny line, in a way. But somehow you don't feel like laughing. It's no secret that Petty recently went through a painful divorce, parting from his wife of many years, Jane.

"Yeah, all that creeps in, doesn't it?" Petty's trademark slow grin dawns over his features, signalling that it's all right to talk about this, that the worst is over. "This record was coming from kind of a rough time for me. I got pretty depressed for a long time; [a divorce] will do that to you. And I couldn't work, really, when I was that depressed. After the long tour we did for Wildflowers [Petty's 1994 solo album], I spent a whole year not doing anything. I kind of came down to earth. You know, that awful period where you have to assess your life. What went wrong and right. I'm kind of over it now. Getting back to work was good therapy in a way."

Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers

Interview by Jim Ladd | Edited by Melissa Blazek

The Album Network - April 16, 1999

April 1 of this year was the 25th anniversary of the day Tom Petty and a ragged band of young musicians departed Gainesville, Florida, in a caravan of cars headed for the mythical lights of Hollywood in search of fame, fun, and a record deal.

It took a few years, but they found all three.

Since that fateful cross-country roadtrip, Tom Petty And The Heartbreakers have perpetuated a distinctive vein of music that's part Byrdsian grace, part fiery orange and purple California sunset, part Southern redneck snarl, part reckless rockabilly elation and all American rock & roll.

Reviews & Previews: Albums

Edited by Paul Verna

Billboard - April 17, 1999

Tom Petty | Echo | Producer: Rick Rubin | Warner Bros 47294

Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers come back swingin' on their latest album, which follows their brilliant -- though commercially disappointing -- soundtrack to "She's The One." As hard-rocking as "Damn the Torpedoes" and as refined as "Full Moon Fever," "Echo" reflects all the facets of Petty's talent, from his jangly side (the Warren Zevon-esque "Accused Of Love" and the Roger McGuinn-reminiscent "This One's For You") to his psychedelic bent (title track) to his power pop sensibilities (lead single "Free Girl Now" and "About To Give Out"). Other highlights include the Neil Young-inspired epic "Swingin'," the Mike Campbell-written and -sung rocker "I Don't Wanna Fight," and the brooding "Room At The Top." Seemingly energized by a burst of created inspiration and by their decision to play small venues, Petty ad the band are in rare form -- a veteran rock group at a new peak. An album that deserves a long and steady run at rock radio, with crossover potential at adult top 40 and triple-A.

MP3.mess: Petty Single Pulled From Net

By Eric Boehlert

Rolling Stone #811 - April 29, 1999

Have MP3 files become so controversial that artists and labels don't even want to talk about them? In March, as sort of a goodwill gesture toward fans -- and as a way to boost the buzz on his upcoming album release -- Tom Petty posted his new single, "Free Girl Now," on MP3.com, the Internet's largest clearinghouse of downloadable music files. It was a bold move considering the unspoken agreement among major labels not to allow acts to post MP3 files, particularly for new songs, until there is a way to contain the technology.

Editor's Note: Thanks to Susan Molls for lending me this magazine for scanning.

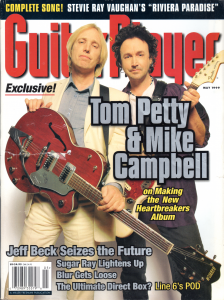

Heartbreaker Hideout In The Studio With Tom Petty & Mike Campbell

By Art Thompson

Guitar Player - May 1999

After more than two decades of crafting hit records and packing concert halls and stadiums, Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers are certified superstars. But, compared to say, the Rolling Stones or U2, there's something more down to earth about the Heartbreakers. Perhaps this is due to the vivid realism of Petty's lyrics, or the band's unpretentious, blue-collar sound, or the stark authority of Mike Campbell's guitar playing. One thing is clear: The Heartbreakers' songs still resonate with their fans, many of whom have supported the band since it burst on the scene in the late '70s.

10 Questions for Tom Petty

By Jaan Uhelszki

MOJO -- May 1999

What's your fascination with San Francisco? Two years ago you staged 20 shows at the Fillmore, and now you're here for seven days.

I thought the Fillmore would be the best place. The audience here is much more forgiving; they let you experiment. We wanted to play a residency, which we hadn't done since 1970. When I first met Mike [Campbell] and Ben [Benmont Tench], we played a residency in this club in Gainesville, Florida. It proved very rejuvenating, making us feel good about the band, that we should carry this thing on a little further.

This time we took that inspiration into the studio with us. It felt like we had a really good little rock'n'roll band. We tried to arrange the music to where we could get it mostly down in one pass. We didn't have anyone in the studio with us. Mike Campbell did the engineering – he'd literally punch 'Record' and turn his guitar on and then we'd go. We did about 25 tracks that way. Mike and I had no idea which the best tracks were, so we brought Rick Rubin in and he helped us sort it out and finish the record off.

For years people thought there might not even be a Heartbreakers. Now you're with them again.

I never thought that. I always thought we'd come through. We did lose Stan [Lynch, drummer], which was a big part of it. That was a major change, so this is Mark II Heartbreakers. I thought I saw Stan from the balcony when I was playing the other night. I looked up and said, "Oh my God it's Stan." But it wasn't. 'The Waiting' always reminds me of Stan when I hear it, because he's the only drummer in the world who could play it. He played very lyrically. That record is completely him. I have never played it since he's been gone. I heard a record that Linda Ronstadt did of it, and she did it very well. I really think I'd quit if I had to play with a back-up band or studio guys. I'd quit. I'm too spoiled. I'm in a good group. I really think they think I'm just a member of the group.

Yet you have your own dressing room – doesn't that mean you're not just another band member?

I only got my own dressing room a few years back. And that was only because I demanded it. They could all have them too if they demanded it. I just need privacy sometimes. I've got more people looking for me, and I have to get away from it all. People who are back there can really drain you before you even get on the stage. I just hide out.

You have a one-time Stooge in your band, Scott Thurston, who played piano on the infamous Metallic KO gig. Is he now an official Heartbreaker?

He is really a Heartbreaker. I don't know if we've ever told him he is. He's been around 11 years now, but he's still the new guy. I love him. He's really becoming my alter ego. He's so talented, and has added a lot of morale to the band. It's nice to have someone come in and say, "You guys are good. You should realise it, and cherish it."

What with hobnobbing with people like Dylan, or recording with the Traveling Wilburys, you seem to be the missing link between the common man and the gods...

I'm seven years younger than them. They're like my older brothers. I was telling a friend of mine the other day how odd it is that I never sought out any of those people, any of my heroes. Somehow the ones that really matter to me, I got to become really good friends with. It's embarrassing. I never mention my friends to people because they think I'm bragging, but it is kind of cool. And I've always been upfront with them about how cool I think it is.

They've been a big help to me in. many ways. Especially George [Harrison] because he's been through all this. I don't have an older brother, and he's always been there to advise me. He'd tell me, "It's like this," or says, "I wouldn't take that seriously at all." It's an unusual way to live sometimes, and to know someone who has been through it, it's great.

I heard about a show you did with Dylan outside of San Francisco; when the stage was darkened during a break, Bob Dylan fell over. You rushed over, looked down, and reported to your band, "Bob Dylan is dead."

Did I really say that? [Gives a quizzical look, as if to confirm] I remember that show, what a night! Me and Stan got in a big fight, and I left the stage. Stan was wound-up about something, and he gave me the finger during the show. I just took my guitar and walked off. Left. They didn't know what to do. And I guess Al Kooper sat in, and they just carried on with Al. I went to my dressing room really mad, I wouldn't come out. Then Bob came in and said, "Come on, come back. John Lee Hooker is here and he's going to play. Come on. Let's go play with John Lee Hooker." I was still mad, but I went back to the stage. Then John Lee Hooker came out and kicked our asses. He was just transcendental. I remember Bob walking across the back telling us, "Don't change chords with John Lee Hooker, he doesn't change chords." And Bob fell over. That was some night.

You're doing some blues covers now, and things I imagine you listened to in Florida as a kid. But I always pegged you as a British Invasion type. Did Florida bands have any impact on you?

I was a big British Invasion kid. Our music was all built on that. And then we used to play a lot with Lynyrd Skynyrd when we were Mudcrutch, before any of us had made records. I saw their music taking off towards Led Zeppelin; we were moving in another way. We respected them, thought they were good. And we loved the Allmans. The Allmans was the first band I ever saw, but they were called The Escorts. There was four of them, and they wore Beatle suits and Beatle haircuts, and they just played Beatle music. I thought they were great. Then they started to put Ray Charles in and stuff. And then I watched them move into that Allman Brothers Band thing. That was great, too. But that wasn't what we thought we should do. It became so immensely popular down there that people didn't like us.

It was a problem for us. We drove up to Capricorn Records – I remember hanging around the studio with the Marshall Tucker Band who were making their first record and invited us in-and we sat around all day and waited for someone to listen to our tape. And the answer was, "It's too British." So we decided then we were going to California. Florida wasn't the place for us. We'd done everything we could do there. We had a huge following. We could do a thousand people. But it wasn't going anywhere. So in 1974 we packed up and moved.

Your house burned down a few years ago; you've said that that was a watershed for you, and that you didn't write any angry songs afterwards. Can you explain why? Was the fire some kind of deeper metaphor for you?

Yeah. Without getting poetic, that's what it was. It was so vicious and angry it completely scared all of that out of me. I didn't want to do anything except sing really light, happy music after that. I didn't know this while I was doing it but, in retrospect, I wanted to go to some much tighter place. I was really glad to be alive, like someone who had survived a plane crash. If you've ever had anybody try to kill you, it really makes you re-evaluate everything.

They never caught whoever set fire to the place. The funny thing was I kept insisting it was an accident, telling the investigators, "Who'd want to kill me?" And then 10 people confessed to the police. None of them did it, but they wanted to confess. Fortunately I left on a tour days later, so it was all contained on the road.

I think knowing someone was maybe trying to kill me revitalised me. I came out of it in a good spot. It just made me glad to be alive.

When you hit your hand into the wall after recording Southern Accents, was that also a turning point?

The hand thing was sort of embarrassing when I look back, because I broke it in a fit of temper, and temper is not good. And I think the temper was fuelled by drugs and alcohol. It was a dumb thing; as dumb as being a football hooligan. I was pissed off, frustrated and I really, really, really, really broke my hand. I pulverised every bone in it. It was just powder.

Two years ago I was learning to kick box, and I fell and broke my arm – the same arm as the hand. When I went into the hospital they X-rayed it, and every doctor who would walk in, even doctors' who weren't treating me, would see the X-rays and go, "Wow! Look at this!" It was all the metal in my hand. "Come here. Look at this." I'd hear it all day long. No-one was paying any attention to the arm. It was all the metal in the end of the hand. It's all wires and studs. But I've never set off any alarms at the airport. Better than that, my hand works really good. It was a long operation, and a long recovery, but I always thought it would come back. I was never worried about it.

I'm better at controlling my temper now. I think.

I always worry about my own temper. I don't think I could keep a gun in the house.

They won't let me have one. I've had mine taken away. The police took it because I'd just start shooting. I wouldn't shoot at people but I'll go out and kill a tree. My dad always had guns; I'm good with a gun. I really like shooting, and when I'd get mad. I'd take a gun and kill some inanimate object. But, finally I got it taken away from me because I was disturbing the peace. I think it's good. It's too dangerous. You don't need it. But I do shoot targets.

Music: Echo

By Christopher John Farley

TIME - May 10, 1999

Tom Petty, an old-school rock 'n' roller to be sure, comes off almost as an endangered species here: cornered, and at times a bit lonely and afraid. Still, Petty evokes rock's glory days with fresh vigor on this CD. His voice seems comfortably worn, ably evoking Bob Dylan's articulate whine and Neil Young's angelic, countrified croon. The songs on Echo don't mess with the form much: they arrive, they rock, they leave. This CD isn't a knockout, but it has punch.

Random Notes

By Anthony Bozza

Rolling Stone #812 - May 13, 1999

There's no reason to change a good thing: Two years ago, Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers preceded their world tour with a twenty-night residency at San Francisco's intimate Fillmore Auditorium. So they decided that before getting lost in the blur of this summer's stadium tour, they'd return to San Fran -- this time for seven nights -- packing quality opening acts: Lucinda Williams, War, Taj Mahal and Bo Diddley. Petty and the band covered every phase of their twenty-year career as well as tunes like J.J. Cale's "Call Me the Breeze," the Tornadoes 1962 surf classic, "Telstar," and "Little Maggie," by pioneering bluegrass pickers the Stanley Brothers. "It's hard to play a Stanley Brothers song to a crowd of 20,000," Petty said. "But in the Fillmore, you can get it over." The Heartbreakers also debuted songs from their latest, Echo, including "Swingin'," a slow harmonica blues, and "Free Girl Now," a Petty rocker that will be the album's first single. "Residencies are kinda cool -- it's a good thing for your band," he said. "It really unified us, let us hone our material and try lots of things we wouldn't have been able to do in a hockey rink."

Performance: Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers | Irving Plaza | April 11th, 1999 | New York

Review by Anthony DeCurtis

Rolling Stone #813 - May 27, 1999

Opening for Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers twice during their three-night stand at the Irving Plaza, Bo Diddley felt compelled in one song to rap. More than a nod from one master of the African-American street-rhyming tradition to a younger generation, it was a veteran showman's attempt to engage the music of the moment.

If Petty felt any similar impulses during his two-hour-plus set, it was nowhere in evidence. With rollicking defiance, he stuck squarely to his own two decades of hitmaking and the Fifties and Sixties nuggets that inspired him. "I won't back down," he sang, cranky and independent-minded as ever, and he wasn't kidding.