The Sanctity of Music

Billboard - October 14, 2017

On July 2, 2016, Billboard editors wrote an open letter to congress, in response to the mass shooting at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Fla., on June 12, 2016, and the killing of singer Christina Grimmie by a gun-wielding stalker two days earlier. The letter, which was signed by over 200 top music artists and executives, asked Congress to close the deadly loopholes around gun regulation that put so many lives at risk.

Fifteen months later, we awoke on the morning of Oct. 2 to news of another mass shooting in a space where music fans had gathered. Fifty-nine people are dead and over 500 injured as the result of an attack on concertgoers at the Route 91 Harvest festival in Las Vegas. Using a semiautomatic rifle he had legally modified to fire at a faster rate, the shooter targeted a crowd watching Jason Alean's Sunday night performance. Because the shooter was positioned outside of the festival ground, this tragedy was not a venue security issue—this was a gun safety issue.

It is unacceptable that so little in our country has changed since the Pulse tragedy. It is unacceptable that our nation must continue to search for a sane and safe end to gun violence.

There is something especially obscene about violence committed in a place of worship. The murders of nine members of the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church by a white supremacist in Charleston, S.C., is perhaps the most heinous contemporary instance. Live music is often fundamental to worship. A concert, like a church, can be the vessel for communion among strangers. Communities spontaneously arise at stadiums and small shows alike. A concertgoer becomes part of a shared experience, and for a few hours, everyone in that venue is in tune with each other. Keeping these spaces safe is crucial.

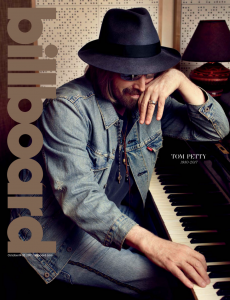

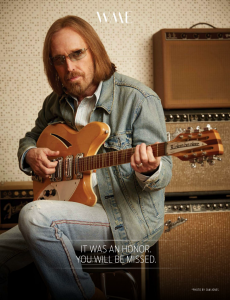

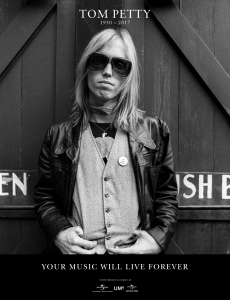

The bonds between people experiencing live music together are as fragile as they are powerful. On Oct. 2, we lost Tom Petty, one of the most celebrated live-rock mainstays of the last 40 years. His shows brought millions together across his career, and his timeless songs will be covered for years to come. Sadly, Petty will never perform again. But even under the specter of possible gun violence, live music will persevere. We all must work to preserve it. We need out elected officials to protect it.

We live in terrifying, difficult times, but music makes community. "You belong somewhere you feel free," Tom Petty sang on "Wildflowers." In an ideal world, we have each other and we have music to help us find that freedom. Anything less won't do.

Ross Scarano, VP Content

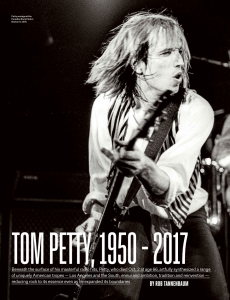

Tom Petty, 1950-2017

By Rob Tannenbaum

Billboard - October 14, 2017

Beneath the surface of his masterful radio hits, Petty, who died Oct. 2 at age 66, artfully synthesized a range of uniquely American tropes—Los Angeles and the South, ennui and ambition, tradition and reinvention—reducing rock to its essence even as he expanded its boundaries

In spring 2013, while he was recording Hypnotic Eye, now his final album with The Heartbreakers, Tom Petty was prepping for a tour with the band, and he was bedeviled by the setlist. "The audience always likes it if you play the hits," he told me. "I feel we have more to offer than that." The set changed each night on that tour, but for the most part Petty bypassed a lot of his best-known songs, from "The Waiting" to "You Don't Know How It Feels." Some nights he even skipped his two signature songs, "Free Fallin'" and "I Won't Back Down."

Petty had resolved to stop acting like a human jukebox. It was consistent with the way he lived his life and drove his career: Figure out what you want and do it. Damn the torpedoes.

Aside from musical ability, Petty's great gift (and occasional curse) was a determination that sometimes turned ruthless. In Runnin' Down a Dream, director Peter Bogdanovich's 2007 documentary, Petty describes his band's beginnings in its hometown of Gainesville, Fla. With a mix of pride and shame, Petty says he convinced guitarist Mike Campbell and keyboardist Benmont Tench to drop out of college and play music full-time. Years later, when he needed a bassist, he stole one from his friend Del Shannon's band, shrugging when Shannon asked him not to do it. He put his career in jeopardy by twice going to war with MCA Records—winning both times. "When I felt any sort of injustice had been done to me, I could erupt into absolute rage," he told MOJO magazine in 2010.

Petty earned every inch of his lizard skin. He described his dad, a charming, carousing good ol' boy, as "very abusive." As early as fifth grade, Petty was a self-described weirdo because of his obsession with music. In an era when every Gainesville musician was imitating The Allman Brothers and playing long jams, he wrote concise, British Invasion-style songs. By his own account, he was a "geeky, artistic kid," a striver with his eye on the West Coast and no interest in the two local hobbies, hunting and fishing. "In the South, I always felt a bit like a duck out of water," said Petty.

He was glad to have grown up there, because being surrounded by R&B and country music made his band tougher and sharper, he said. "When we came to L.A., we thought we'd have to come up a few notches to compete. And our first impression of the local groups was, 'Wow. These guys suck!'" Petty recalled with a laugh. But, he pointed out, unlike the rest of his family and friends, he didn't have a Southern accent. When I suggested he had ditched the accent as a way of shedding the South, he agreed.

Petty was a loose, forthright guy who laughed a lot, but he was also peevish and held tight to grudges. He recalled, and not affectionately, a Los Angeles Times article about the city's all-time top groups, in which he and his band were excluded because they started in Florida. "That's kind of a shitty feeling. The Byrds all came from different places. So did Buffalo Springfield. Jim Morrison came from Florida, for Christ's sake." It pained him to be shunned as a carpetbagger in the city he had idolized and where he lived for almost 40 years.

If denim could start a rock band, it would sound like Tom Petty. In his songs, he drew heavily on The Byrds and Buffalo Springfield as well as The Animals and The Rolling Stones. His most frequent lyrical tone was a wounded perseverance: "You can stand me up at the gates of hell/And I won't back down" wasn't just a refrain, it was his mission. His choruses relied on firm, declarative phrases: "You don't have to live like a refugee," "Don't come around here no more," "You don't know how it feels to be me." At first glance, his songs seemed rudimentary, but Petty deployed contradictory ideas and feelings almost like jump cuts in a movie.

Petty was less artful than other songwriters in hiding influences — has any singer ever been called "Dylanesque" more often or more accurately? — but he in turn became an influence on anyone who grew up on FM radio in his heyday. Nearly every country or alt-country band was influenced by him, as were John Mayer, The Wallflowers and The War on Drugs. Half of Sheryl Crow's biggest hits could be Petty songs, as could Elton John's "I'm Still Standing." Like The Beach Boys, The Doors and a few other bands, Petty made California a universal idea.

Petty was adept at playing possum, the Southern tradition of passing yourself off as a simpleton even when you're not. But it was one of the only things he kept when he left the South. "We felt much more at home, musically, when we got to L.A. If I'm honest, we're a California band," he told me. "We're probably the last link to that long line of bands that came off the [Sunset] Strip. We're probably the end of the line."

'There's Nothing Like Being in a Band'

By Alan Light

Billboard - October 14, 2017

Tom Petty was never shy about fighting for his artistic vision, but his reward was the joy of jamming with his friends — in The Heartbreakers, Mudcrutch and the Traveling Wilburys

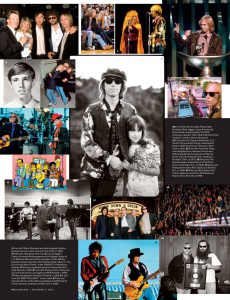

"There's nothing like being friends and being in a band," said Tom Petty. "That's the most attractive part of it to me. When I saw The Beatles on Ed Sullivan, I'd think, 'Those guys look like they're all friends and they're having such a good time.' And that's really important to be a good band."

As he was telling me this in 2014 at his sprawling home in Malibu, Calif., I thought back to 2008, when I watched Petty reheasing with his recently reassembled second band, Mudcrutch. Petty beamed as he and a group that had broken up 32 years earlier — though two of its members, guitarist Mike Campbell and keyboardist Benmont Tench, continued to play with him as the core, The Heartbreakers — bashed through a version of "Shake, Rattle and Roll" in his Van Nuys rehearsal space. A few months earlier, Petty had headlined the Super Bowl halftime show, but right then he looked content with the simple pleasures of playing bass and singing harmony in a rock'n'roll band.

Petty never seemed to lose the joy and wonder of being part of a musical group. With his death, so much of the focus has (rightly) been on his extraordinary songwriting, but Petty was also one of rock's great bandleaders, maintaining the airtight versatility of The Heartbreakers for 40 years while also juggling the reunited Mudcrutch and, of course, The Traveling Wilburys.

Campbell spoke of Petty's talent as a frontman when I interviewed him in 2014. "At the end of the day, it's always Tom's choice," he said. "With the label or management, he has good antenna for weeding out bullshit and phoniness and keeping everything honest."

Not that it was an easy role. As explored in Warren Zanes' excellent Petty: The Biography from 2015, the pressures of fronting weighed heavily on Petty, particularly the departures of drummer Stan Lynch, who quit in 1994 over longstanding personal and artistic differences; and in 2002, bassist Howie Epstein, who was fired in part due to his heroin use — not long after Petty had kicked his own addiction to the drug. (Epstein died from an overdose in 2003.)

"I never really wanted to be up front," Petty said in 2014. "[In the beginning] I was the bass player, but I was the one with the record deal, and the record company wanted me up front...I didn't really understand all that entailed at the time, but that's the way it went."

Petty's leadership kept The Heartbreakers a stable unit. Its latest iteration looked a lot like its first, and even its never members—drummer Steve Ferrone, who replaced Lynch, and utility player Scott Thurston—had been with the band for over 20 years. Petty even replaced Epstein with original Heartbreakers bassist Ron Blair.

"They're very quick to tell me if they don't agree with me or if they have a better idea," Petty sai of his group in 2014. "So in our minds, we don't really see a difference between us and a band like The Stones."

Putting Mudcrutch back together, Petty said in 2010, sprang from "a random thought: 'I really liked that band. I wonder what it would be like to get them together.'" Petty woul later express delight about this unlikely reunion that included co-founder Tom Leadon, with whom Petty had formed his first band, The Epics. "I loved being with those people," he said. "A very happy bunch of people and old, ol friends."

He even described The Traveling Wilburys—which saw him collaborating with George Harrison, Bob Dylan, Roy Orbison, and Jeff Lynne — as having a genuine band dynamic. "We were all in the same circle, and the group just naturally materialized," he said in 2007.

Petty was never shy about fighting for his vision in the studio or with the music industry. His reward, then, was that feeling of camaraderie and collaboration, whether with his old crew from Gainesville or his new peers in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

'He got to my sexuality before I really understood it'

By Liz Phair

Billboard - October 14, 2017

My love for Tom Petty was pure teen-idol love. I can name at least three guys who had shades of Petty going on, and that was a tipping factor in whether I dated them.

His voice went right through me. You didn't expect such a low, deep, authoritative voice to come out of a fair-haired guy. He looked sensitive, but I'll tell you this—he disturbed me. He got to my sexuality before I really understood my sexuality. He was one of the first pop idols I would have dreams about. It wasn't like "Oooh, Luke Skywalker!" where you'd kiss the TV. There were parts of him that were not Prince Charming. Like "God, this is uncomfortable! I don't understand your teeth!" You could tell that if you dated him, you'd be like, "Are you ever going to call? Where are you?!"

And yet somehow you just trusted him. Like, if you were hanging out in his house, he'd probably have a lot of books and he shy about it. It was clear that he was 100 percent aware of what you were feeling as a woman. He just wasn't going to give you what he wanted. In "Free Fallin'," if you think about it, he's kind of being a douche, but he's also being honest. He's singing very soulfully about not being willing to change.

The 'American Girl' Dream

By Gavin Edwards

Billboard - October 14, 2017

One early song articulated Petty's great theme—that even impossible hopes sustain us—and captured a mood across multiple generations

At the very end of the self-titled debut album by Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers, after 27 hit-or-miss minutes of swampy rock'n'roll, comes an electric shock. Two guitars make a holy chiming sound over a Bo Diddley-style beat, soon followed by Petty drawling, "Well, she was an American girl/Raised on promises." The song was "American Girl," and although it wasn't a hit on its release—it didn't crack the Billboard Hot 100—through the years it became the anthem Petty had intended, a modern standard for millions of American girls (and boys).

Petty considered "American Girl" to be the first installment in a long-running series of songs about people longing for something bigger than their current existence. His sympathy for the title character came naturally: When he wrote the song, it was only a few months after he had left small-town Florida for a music career in Los Angeles. Not yet a rock star, he was living in an apartment next to the freeway in Encino, Calif. He used to tell friends that the sound of the traffic was actually the sound of the Pacific Ocean—a joke that got a Florida route number and became the lyric "She could hear the cars roll by/Out on 441 like waves crashing on the beach."

Early on, Petty figured out something crucial that made his music endure: that songs about people striving for their dreams are more powerful if the heroes don't get what they want. The American girl may never live next to the ocean. Even the losers get lucky sometimes, Petty allowed—but then he put the happy romance of that song in the past tense. WHen Petty wrote about a day in the sunshine, he had to puncture its fantasy immediately: "Runnin' down a dream/That never would come to me." All those songs feel joyful anyways, not just because The Heartbreakers could play like their amplifiers were on fire, but because Petty cherished the battle more than the victory.

Guitarist Mike Campbell said in 2008 that recording "American Girl" was the greatest highlight of his career: "[W]e had found something really special that no one else could do."

The song has been covered by artists from Taylor Swift to the Goo Goo Dolls—not to mention The Strokes taking the central riff for a joyride in their breakthrough hit, "Last Nite." In 1985, when Petty and The Heartbreakers played the biggest show of their career at the Live Aid festival, they started their set with "American Girl." And at Petty's last show ever, on Sept. 25 at the Hollywood Bowl, it was the final song he played.

"American Girl" sets the scene as Jennifer Jason Leigh returns to school in the opening of the 1982 film Fast Times at Ridgemont High. It underscores the triumph of Amy Poehler in Parks and Recreation when she finally launches the Harvest Festival. Just this year, it was an ironic counterpoint to the uncertain fate of Elisabeth Moss in the closing sequence of the first season of The Handmaid's Tale. It rings true on all those soundtracks, but it has never been better used onscreen than in Jonathan Demme's 1991 thriller, The Silence of the Lambs. A young woman (Brooke Smith) drives home at night, singing along to the song, keeping time on the steering wheel. She is moments away from a terrible fate, but while she listens to this song, she is free.

A Classic, Unclassifiable Rocker

By Sasha Frere-Jones

Billboard - October 14, 2017

Petty's complex, sui generis songwriting did not neatly fit into the catch-all genres to which he was consigned late in his career

On July 14, 1978, with New York's punk scene well into a second wave that wasn't all that punk, Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers played the Palladium on East 14th Street, a nightclub that has since been turned into a New York University dorm. Two days later, music critic Robert Palmer wrote about the band in The New York Times: "They are too melodic and '60s-influenced to be called punks, too intense and jangly to be labeled pop-rock, too basic in conception to fit into either the jazz-rock or art-rock categories. Perhaps they are new wave, although that term is vague enough to be virtually meaningless."

Palmer's inability to pick just one sound for Petty was not a failure but the evidence of close listening. Petty spent 40-odd years using the simplest iterations of voice and guitar to write what sounds like songs beneath other songs. Much of it was tagged as classic rock, which speaks to a world less optimistic than Petty, who thought rock was as eternal as theater. Who calls Shakespeare "classic theater"?

In a 1999 interview with Charlie Rose, Petty talked about his Echoes album. "I guess they would call this a classic rock album. I don't really like the term 'classic' too much," he said. "It makes me feel like there's nowhere to go. I think there's a lot of places to go with rock, still. I don't think that the whole story has been told or the whole song has been sung. I still think there'll be innovations within the form."

Rock only got to be classic because a writer like Petty could hear which parts of rock made it classic. His music endures because it never calcified, unlike that of so many legacy artists with whom he was pigeonholed in his later years.

So many of Petty's songs sound like the elements themselves, uncut substances that could be used in almost any genre. The very first Petty single, "Breakdown," from 1977, was one of the sneakiest things he released. The song has more electric piano than guitar, and when he played it live, Petty often interpolated Ray Charles' "Hit the Road, Jack." Play it alongside Boz Scaggs' "Lowdown" or something from Tom Waits' Small Change album, and you'd think Petty was angling to be a next-stage soul singer. Petty never wrote another song like it, but "Breakdown" placed a pylon on his road, making it clear how wide his field of vision was.

"Jammin' Me," from 1987, is a reaction to pop culture overload (more or less rewritten by Bruce Springsteen in 1992 as the lesser song "57 Channels [And Nothin' On]"). At the time, it reminded many reviewers of The Rolling Stones' "Start Me Up," but in 2017, hearing the guitars and drums line up, the AC/DC comes through clearly. This song could get much louder without any awkwardness.

1991's "Learnin' To Fly" lands far from "Jammin' Me" on the style spectrum, showing again that three chords and a topline were fuel, not restraints, for Petty. If there is a bridge between Tracy Chapman's "Fast Car" and Dixie Chicks' "Wide Open Spaces," this song is it. Move from the Rickenbacker to an acoustic, and the genre changes. It is this flexibility that a term like "classic rock" conceals.

"You Don't Know How It Feels," from 1994, paired Petty with someone else who studies the DNA of songs, carefully and repeatedly: Rick Rubin. Steve Ferrone's drums are the loudest of any Petty recording, which doesn't mean they keep Petty from his mission. He knew his territory, and it didn't share a border with dance or hip-hop. But he could easily cross into guitar-heavy areas without blinking. Those borders were his. Like new wave, though, "classic rock" is a fairly meaningless term without someone to complicate it every few years. That job is now open.

'He was very humble, beautifully shy'

By Kim Basinger

Billboard - October 14, 2017

I did the "Mary Jane's Last Dance" video [in 1993] for one reason: Tom Petty. I didn't even care what it was about—I was just blown away when he called. Then I heard the music, and I was so in love with the song.

The director (Keir McFarlane] was a gruff guy; it was kind of like, his way or the highway. And I always found Tom to be incredibly sensitive and sort of a backseat guy. He was just very humble, beautifully shy. I'm not the most outgoing human being in the world, and I thought, "I'm shy; he's shy." But as the story really unfolded and this director kept saying, "Look, you have got to really play dead—all your weight," we laughed so hard. I just honestly couldn't keep it together sometimes! Tom had a great sense of humor. I remember getting out of the pool that day and just being so glad it was order, but so proud that I had worked with him."

'His music is filled with intelligence, history, humor, nostalgia, heartache, love—he captures life experience with his songs.' - Tom Cruise, who sang "Free Fallin'" in the 1996 film Jerry Maguire

The Punk In Petty

By Lizzy Goodman

Billboard - October 14, 2017

He found mainstream mega-success, but that didn't change the proudly weird outsider spirit at his core

I watched the first Tom Petty song I ever heard: 1993's "Mary Jane's Last Dance." In the music video, a quietly amused guy in a top hat danced with the pretty blonde from Batman who appeared to be dead. He seemed both playful and dangerous, and to preteen me, a peer of Björk, Kurt, Courtney, PJ and Eddie—this gang of rock'n'roll characters who helped kids like me reframe our insecurity and oddness as freeing, not humiliating.

Petty was born in 1950. His childhood was steeped in Elvis and cowboy movies, his adolescence in the era of '60s rock and radicalism. But the decade of his formative creative galvanization, the 1970s, was about alienation, disenfranchisement and disillusionment. Petty's wry yet romantic songwriting matched the emotional pitch of his mid-baby boomer mini generation: too young to have ever believed that all you need is love, too old to really embrace Gen X's ironic detachment.

Though he became a classic rock icon, Petty's attitude was always punk. He was a freak, angrier and weirder at his core than his omnipresent radio hits would suggest. The first Heartbreakers album came out in 1976, the same year as the first Ramones record, and by the late '70s ascendant Petty was racing in the same heat as Blondie, Patti Smith, and Talking Heads—American punk rock's first graduating class. His sound blended the primal roots-rock of his youth with the defiant sneer that befitted Vietnam and, later, the Reagan era. But the absolute essence of Petty's aesthetic tapped first and foremost into a sense of surrealist rebellion. "We had to be in the new wave, because we weren't in the old. I just don't like clubs," Petty says with a smirk in Peter Bogdanovich's documentary, Runnin' Down a Dream. "We didn't join no clubs. We're our own club."

Don't Do Me Like That

By Fred Goodman

Billboard - October 14, 2017

After signing away his publishing rights early on, Tom Petty worked the angles for years to steer his career—and keep the money flowing in

Tom Petty sang "I Won't Back Down" with a raffish drawl. But when he delivered the same message to a record company, it was with the conviction of an artist protecting the integrity of his work—one who became increasingly cognizant of both his creative and financial leverage and adept at controlling his career.

Petty was first signed to Shelter Records—a boutique label co-owned by Leon Russell and producer Denny Cordell—as a member of Mudcrutch. After releasing one single, Shelter opted to drop Mudcrutch but keep Petty. His initial singles with The Heartbreakers, "Breakdown" and "American Girl," failed to chart, yet he quickly built up a strong following in England, and the band's popularity as a live act helped his two albums for Shelter go gold.

That first flush of success proved far less lucrative than Petty expected. Particularly irksome was the realization that he had signed away all his songwriting and publishing rights for $10,000. "I had no idea 'd never make money if I did that," he told Rolling Stone in 1980. When Shelter's distributor, ABC Records, was sold to MCA in 1979, Petty sought to break the contract. He said he was motivated by the idea that "I could work my ass off for the rest of my life, and for every dime I saw, the people that set me up would've seen 10 times as much."

MCA and Shelter sued Petty for breach of contract, and Petty and his managers, Tony Dimitriades and Elliot Roberts, ratcheted up the stakes by having the rocker file for bankruptcy protection—a move that could force a court to readjust all of Petty's business arrangements, including the recording contract. Designed to throw a scare into the industry (if Petty was successful, fellow artists might see bankruptcy as a useful tool for renegotiating and breaking contracts), the tactic succeeded in getting Cordell to settle out of court. "It may have been a sham in some ways," Petty admitted to his biographer, Warren Zanes. "But...[Cordell's] lawyers figured we'd out-lawyered them."

MCA mollified Petty with a new imprint, Backstreet Records, and a deal that reportedly included a $3 million guarantee, and Petty regained his publishing rights. The Heartbreakers' first Backstreet album, Damn the Torpedoes, went to No. 2 on the Billboard 200 and was certified triple-platinum. But the honeymoon proved short-lived. When MCA sought to make 1981's Hard Promises its first $9.98 release, Petty staunchly resisted, even suggesting he would retitle it Eight Ninety Eight. MCA "couldn't see that raising the album's price wouldn't be fair," he told The New York Times.

By 1987, Petty was itching to move on. "I had written this song, 'Free Fallin'," he recalled earlier in 2017, "and taken it to my label, MCA, and they rejected the record." Not long afterward, when the idea for The Traveling Wilburys was incubating, Petty spent an evening with George Harrison at the home of Warner Bros. Records chairman Mo Ostin. "Dinner ended and George said, 'Let's get the guitars out and sing a little bit. Let's do that "Free Fallin'"." [Warner Records president] Lenny Waronker said, 'That's a hit!' I said, 'Well, my record company won't put it out.' And Mo said, 'I'll fucking put it out.'"

Petty then signed a secret deal with Warner Bros., reportedly with a $20 million guarantee. MCA agreed to scrap the last album in his contract in return for a greatest-hits package featuring two new tracks; one of those songs, "Mary Jane's Last Dance," subsequently became a hit. If it chafed to have Petty spirited away by Ostin—his first album for Warner Bros., Wildflowers, went triple-platinum—then-MCA Music chairman Al Teller likely found some consolation in seeing Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers Greatest Hits sell a reported 12 million copies.

'The good old Florida boy was still there'

By Bill DeYoung, The Gainesville (Fla.) Sun arts editor, 1982-2002

Billboard - October 14, 2017

When I got to The Gainesville Sun, Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers' meteoric rise was happening. They were the coolest thing to ever come out of Gainesville, and I made it my mission to make sure the world knew where they came from. I mean, he was an L.A. rock star for sure. But if you just scratched the surface a little, the good old Florida boy was still there. He was a man without pretension—it's just the way you grow up down here.

At the end of the day, the [speaking manner] never changed; the laconic humor never changed. I can do his voice pretty well at this point; a little bit of slur, you don't move your teeth much, you talk through very tight lips.

Everybody you meet of a certain age here has a Tom Petty story: "I knew Tom at Bishop Middle School," "He dated my sister," "He was the weirdo kid who smoked a lot of pot." He's part of the shared cultural heritage of Gainesville. People are still very proud that you can look at him and say: "Here's a guy who's just like me—and it actually worked!" It wasn't luck, it wasn't some Svengali. This guy was just fucking talented and it all happened, and he came from here, and he never forgot that.

'He made me think, "Maybe I can do this"'

By Lucinda Williams

Billboard - October 14, 2017

I opened for Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers in 1999, right after Car Wheels on a Gravel Road was released. People didn't know who I was much back then, and it was clear his audience was impatiently waiting for Tom Petty to come out. There was a banana peel thrown onstage at one point. It was pretty brutal! But after two or three nights of this, Tom came out and introduced us: "Guys, I want you to listen. This is an important artist, and you need to be respectful of her and pay attention." That's what won my heart. I had opened up for Bob Dylan and Van Morrison, and it could feel really disconnected and weird. But going out with Tom was like, "Wow, these guys seem to be enjoying themselves!" He made me finally think, "Maybe I can do this."

When I was invited to open for these last Hollywood Bowl shows [in September], it was like everything had come full circle. On the last night, I'd done my set and I still hadn't seen Tom. I went down to his dressing room, stuck my head in, we gave each other a big hug. I said, "Well, I got 'em all ready for you Tom. We rocked, they're ready to go." And as I turned to leave, he gave me this big smile and said, "I bet you did," with that twinkle in his eye. He seemed so good.

Kicking Out The Jams

By Simon Vozick-Levinson

Billboard - October 14, 2017

He knew the arenas wanted to hear 'Free Fallin'." But in a set of freewheeling smaller shows during the past decade, Petty and The Heartbreakers revealed the breadth and complexity of their roots

There's no shame in playing the hits when the hits are as iconic as the ones Tom Petty made throughout four decades. As recently as the last week of September, social feeds lit up with exhilarating footage from the Hollywood Bowl, where Petty and The Heartbreakers concluded their 40th-anniversary tour with three shows stacked with classics like "Refugee," "Free Fallin'," "Mary Jane's Last Dance" and "Learning to Fly"—all sleek hook machines that work as well now as when they were recorded. Petty knew he had one of rock's all-time greatest singles catalogs, and he made excellent use of it in 2017.

But those indelible choruses only tell part of Petty's story. His ability to write that way, with a seemingly effortless elegance unlike any of his peers, was grounded in his deep knowledge of rock history and his finely honed instrumental technique (paired with that of his bandmates, notably guitarist Mike Campbell and keyboardist Benmont Tench). You can hear it in the breadth and depth of The Live Anthology, the four-disc box set the band released in 2009. But better yet, those who scored tickets to the group's rare tours of smaller venues in recent years got to witness it in person.

On one such memorable run in 2013, the band made it through five nights at New York's Beacon Theatre and six at Los Angeles' Fonda Threatre without touching many of its best-known songs. Instead, the group played fast, loose versions of little-heard jewels ("When the Time Comes," from the 1978 album You're Gonna Get It!, appeared for the first time in 33 years in New York) and a diverse array of covers. The setlists slid easily from Memphis soul (Booker T. & The MG's "Green Onions") to Chicago blues (Muddy Waters' "I Just Want to Make Love to You" to Tulsa roots-rock (J.J. Cale's "I'd Like to Love You Baby") to Nashville country (Conway Twitty's "The Image of Me") to California garage rock (The Monkees' "[I'm Not Your] Steppin' Stone]")—brilliantly unraveling the tapestry of American sounds that Petty wove together starting in the 1970s.

Most surprising of all was how freely the group jammed at these shows. Performances of the Grateful Dead's "Friend of the Devil" stretched to seven minutes or more, spinning out into wild, cosmic dances among Campbell's guitar, Tench's organ, and Petty's harmonica. This wasn't a luxury the band often allowed itself on record, where its primary focus remained concise three- or four-minute pop songs, calibrated for maximum joy per second. It was revelatory to see how well the gambit worked in concert, showing off the sheer technical talent that made the group's most popular records possible.

After seeing one of those shows, it was natural to ask why Petty didn't do this more often. Perhaps it found it more fun as an occasional treat. More likely, by that point in his career, Petty would have liked to play such sets for larger audiences but felt it wouldn't have been fair to the arena and amphitheater crowds who paid to hear their favorite radio hits. If Petty felt that tension, his dedication to giving millions of fans what they wanted won out. That's a big part of what made Petty such a unique star: His was one of the least self-indulgent, most generous careers in rock. But put him in front of a smaller room of devoted listeners—the people who wanted the deep cuts and the long jams he so loved to play—and boy, could he deliver.