Editor's Note: Thanks to Susan Molls for lending me the magazine and scanning a page that I stupidly missed.

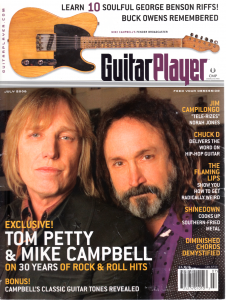

30 Years & Counting

By Art Thompson

Guitar Player - July 2006

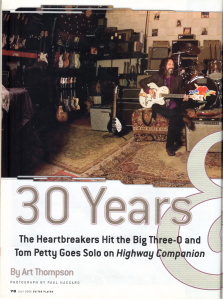

The Heartbreakers Hit the Big Three-O and Tom Petty Goes Solo on Highway Companion

"We were just listening to Buck Owens on the way over here," says Tom Petty as he setltes into an easy chair at the Heartbreakers' rehearsal studio after spending most of the day stuck in L.A. traffic. "I was in this band called the Epics when I was 16, and we used to go out on road trips on the weekends. A lot of times, we'd be driving back from the gig, and we'd pull into these truck stops where I'd hear Buck Owens on the jukebox. I thought he was terrific."

Petty's recollections of hearing the late country star's 45s spinning on a jukebox highlight the long road he has traveled since his earliest days with both the Epics and the country-rock band Mudcrutch -- the group that could give him his first taste of songwriting success, as well as bring him together with the Heartbreakers' guitarist Mike Campbell and keyboardist Benmont Tench. Petty certainly has a lot to reflect on as the Heartbreakers celebrate their 30th Anniversary this year. The band's remarkable run to the top -- which began with the 1976 release of their debut album Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers -- has resulted in 50 million records sold, four Grammy Awards (from 16 nominations), 25 top singles, and more music-industry honoraria than any of the typically self-effacing members of the Heartbreakers probably cares to recall.

Petty's remarkable band dropped onto the scene at a time when rock fans were salivating for some of the primal elements that were AWOL in the bloated rock scene of thje late 1970s. "We probably invented new wave, but we were running ahead of it," says Petty. "I didn't want any label to be put on us, and I was very conscious that we were a rock and roll band and not anything else."

Apparently, that's all that the millions of new riders on the Heartbreakers' bandwagon wanted them to be. Following the 1979 release of their powerhouse third album, Damn the Torpedoes, the band had to suddenly balance their phenomenal success with the challenge of figuring out what to do next. And instead of blowing to bits, as did so many other young groups that had skyrocketed to the top of the charts, the Heartbreakers just kept churning out album after album of great music.

To celebrate the band's 30th year, a couple of exciting projects are in the works. Perhaps the biggest treat for Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers fans is a feature-length documentary directed by famed auteur Peter Bogdanovich. The famously private band members allowed Bogdanovich access that no one else has ever been offered, and the yet untitled film promises to be the most comprehensive overview of Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers ever produced. Principal photography started last year, but, at press time, there was no release date scheduled.

The Heartbreakers' summer anniversary tour is also designed to be an event, with a revolving cadre of famous guest stars. The actual dates weren't confirmed at the time of our interview, but the opening acts are reported to include Pearl Jam, the Allman Brothers, and Trey Anastasio.

Petty is also keeping busy doing the second season of Tom Petty's Buried Treasure -- his weekly XM Satellite Radio Network show -- and voicing the character of Lucky on King of the Hill. Most recently, Petty, Campbell, and producer (and former ELO frontman) Jeff Lynne joined forces to record Tom's third solo album, Highway Companion [American Recordings], a spare but deliciously inviting album that sounds in many ways like something the band might have recorded decades ago. It's a tribute to the consistency and depth of Petty's songwriting, as well as how timeless his songs sound when Campbell applies his magic to them.

How did you wind up partnering with Jeff Lynne again on your new solo album?

Jeff and I were asked by Olivia Harrison [George Harrison's wife] if we would go to New York and induct George into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2004, and we were supposed to play a couple of his songs. Jeff doesn't like to play life, but I talked him into it. The performance went well, so on the trip back I said to him, "We ought to do a track sometime." Then, Mike and I went over to Jeff's house, showed him a tune, and he wanted to cut it right there in his studio. We didn't have a band, so Jeff said, "You play drums don't you?" So I would up being the drummer. Anyway, that first track went really nice, so we just pitched camp at Jeff's studio. I kept dragging out songs, and the next thing we knew, we'd recorded ten tracks. It was just the three of us. Jeff played bass, Mike played all the solos, and each one of us would fill in wherever we could on keyboard and guitar.

Was it your intent to produce a very streamlined sound?

Early on, we decided not to use a lot of instrumentation. I kept saying to Jeff and Mike that I wanted it to sound like a combo. I wanted to leave a lot of space, and not try to fill everything in. Of course, Jeff is a master at recording vocals, and he knows how to make a vocal sound full, even when there are not a lot of different textures around it. We didn't use a lot of keyboards, either. Because this was a solo record, I steered away from anything that was too Heartbreakers sounding.

There's certainly more slide playing than on most Heartbreakers albums.

Mike kept saying, "Do you really want slide again?" I wanted this record to have a distinct vibe, and a continuity of sound, and his slide playing really does that. There's slide on just about every number, but Mike was able to find enough tonal variations to produce lots of textures without the album sounding slickly produced. We've always paid a lot of attention to the textures and characters the guitars create.

There's a consistency in the Heartbreaker's sound that goes back to when you first started, and when you listen to some of the early Mudcrutch songs on Playback, it's impressive how good you guys sounded even way back then.

It's amazing, because I think I was 19 when we recorded some of those songs. We had never really been in a studio before, and we did "Up in Mississippi Tonight" and one other song in four or five hours. They were done really fast, put on a 45, and released in the Gainesville area -- which is where we were from. "Mississippi" did pretty well on the radio. For a local group, we got a lot of play on it, which was cool, because we got to raise our prices a little bit. But we were just kids, and how we did it I have no idea. It's all kind of mystical -- like it was meant to be.

To what do you attribute the Heartbreakers ability to stay together for so long?

We just like to do it. We're probably one of the five top rock and roll groups, and I couldn't think of leaving. To go anywhere else would be a disappointment. But I think the number one reason we've stayed together is that we have become a family over all these years. Me and Mike and Ben go back further than the Heartbreakers -- back to around 1970. I don't have a lot of family of my own, and Mike is the same way, so we have that bond together. We've very much like brothers and we fight like brothers, too. But the band has somehow become bigger than all of us. I see it in a kind of holy way. The Heartbreakers have made so many people happy that it would almost be a sacrilege to turn my back on it.

Do you think the band could make it if you had to start over today?

No, I don't. We were so nurtured by Denny Cordell -- a great producer who had done all these amazing records, such as "A Whiter Shade of Pale" and all the Joe Cocker stuff. He was the secret. He signed us, and he let us play in the studio for a year before we put our record out. If we had just shown up in town, and were told to cut a record, I don't think it would have been that good. We were allowed to grow. The first record we put out did okay, the next did even better, and the third one just exploded.

How is the situation different now?

These days, if a group puts out their first record and doesn't have any success, the record company just moves on to another group. It's more cost efficient or something. The sort of nurturing we got doesn't seem to go on today. Denny was looking at us as a band that was going to have a career, rather than a band that was going to make a hit record. And what got drilled into our heads is that it's not about any particular record, it's about a consistency of work. You want your work to be the best it can be all the time, and you don't want to get caught up in what everyone else is doing, or what is an immediate hit. If you do good work it will take care of you. I think that's what has carried us this far. When you go back and listen to some of those old songs we did, they still hold up. I'm kind of surprised by it, too. I heard "Breakdown" on the radio a few days ago, and it sounded great. That was a really well made little record. And we were just kids. We didn't know we were making something that was going to last for decades.

The Heartbreakers have a very identifiable guitar sound. Can you explain what you do to create that?

Mike and I have a sound we make together that is particularly us, and it doesn't happen when we play with other people. There's something the two of us instinctively do. It's about the way our chords ring, or their voicings, or how our tones work together. It's partly because we've played together for so long, but it's also because we always had to make a lot of racket to carry that sound in a small group. We've learned how to use it to our advantage -- especially when we play live.

What kind of music has inspired you lately?

I really like blues a lot -- especially the stuff on the Chess label by Lightning Hopkins, Muddy Waters, and others. There's something extremely pure and poetic about that music. Some of it is pretty rugged and raw, but there's also something about it that's just beautiful. That's what's speaking to me lately. But I have to listen to so much music these days for my weekly satellite radio show. I go through a lot of stuff putting the shows together -- a really wide range of blues, R&B, rock, and garage rock from the '50s, '60s, and '70s.

How has your setup evolved over the years?

I was using Vox amps for many years, and then I started playing Fender Bassmans, but they sounded a bit too growly for me. Then, I came across this old red Marshall on the road, and I started using that. Last year, we rolled out the old Vox Super Beatles we'd bought back in the band's early days. They make a pretty cool sound, so we tried them again, and we wound up using them on the last tour. But I still kept the Marshall, which I run through a Vox cabinet. I also have another Vox head and cabinet, and I use a footswitch to select either the Marshall or the Vox or both.

What effect has the Marshall/Vox rig had on your stage volume?

I'm probably playing louder now. I try not to, but when you play big places you need a little air movement. A lot of people are putting their amps under the stage and playing through headphones, but I need to feel some air moving. But I'm not slamming it to 10 and trying to kill everybody. I just turn it up enough to where the sound is full and it has some nice bottom.

What is your main guitar now?

I started playing Stratocaster again last year -- mainly early '60s models. I like Teles, Gretsches, and Rickenbackers, but I guess if I had to pick one guitar to get the job done, it would be a Strat. I used about a dozen different guitars on the last tour -- of course, some were in different tunings, and some were acoustics. One of my favorite guitars for recording is an Epiphone Casino. It's a great guitar, but it's kind of tough to take it on the road because it feeds back at loud volumes. Even so, the last time we were in here rehearsing, the Casino is what I was playing most of the time.

Do you often write songs in response to things that have affected you on a personal level?

I'm sure that everything you write probably comes from some place in your soul. I mean, you can only write what you know, so it's all going to creep in there. But I don't often sit down and say, "I'm going to write about this." I just start playing, and things come in. When something feels like it has a nice ring to it, and it connects with me, then I trust it. Sometimes, I'll mean the song six months later, and think, "I know exactly what was on my mind then."

Have there been songs you thought were too introspective to release?

I thought "I Won't Back Down" was too introspective. I was hesitant with that one, because there's not much ambiguity or metaphor in it. It just says it. I remember asking Jeff Lynne -- who produced it -- if he thought the song might be a little embarrassing. He said, "No. It feels great." So I was surprised when it was received the way it was. People are always telling me, "That song helped me through the worst time of my life."

The thing about songwriting is that there's an exception to every rule. It's hard to talk about it generally, because each song is so different. I think my best songs are the ones where you can find different levels of meaning in them. Those are the ones I find the most intriguing, but I don't always write that way. Sometimes, I'll write a linear kind of thing, such as "Into the Great Wide Open," which is just straight-on storytelling. But the ones I really like have a bit of ambiguity. I don't have a method that always works. The process is so random, and yet it keeps happening. I just look up every year or so, and I've got ten more songs. It's not something I work at every day, but I kind of feel that I'm never done writing. I'm always looking for a song.

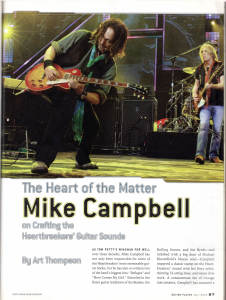

The Heart of the Matter: Mike Campbell on Crafting the Heartbreakers' Guitar Sounds

By Art Thompson

Guitar Player -- July 2006

As Tom Petty's wingman for well over three decades, Mike Campbell has not only been responsible for some of the Heartbreakers' most memorable guitar hooks, but he has also co-written two of the band's biggest hits: "Refugee" and "Here Comes My Girl." Schooled in the finest guitar traditions of the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and the Byrds -- and imbibed with a big dose of Michael Bloomfield's bluesy soul -- Campbell imparted a classic stamp on the Heartbreakers' sound with his fiery solos, chiming 12-string lines, and sweet slide work. A consummate fan of vintage instruments, Campbell has amassed a collection of guitars from the '50s and '60s that would cause most collectors to turn a lighter shade of chartreuse. The difference is that Campbell actually plays all of the rare beauties he owns -- dozens of which sit shoulder-to-shoulder in racks at the Heartbreakers' Southern California rehearsal studio.

With such a vast number of vintage guitars and amps to choose from, how do you go about picking the ones that will sound best for the songs you're recording?

When I listen to a new song -- or hear the band playing a certain way -- I'll instinctively start thinking, "What tone would complement this?" If Tom's guitar is real bright, I might want a darker tone so that we're not fighting for the same frequencies. That might make me reach for a Gibson, or maybe a Gretsch -- which I know will sound somewhere in-between a Fender and a Gibson. If you think of it like painting, each tone is a color. I want a full spectrum in the picture, so I try to fill in the colors that the rest of the band members aren't playing.

You guys certainly helped revive the Rickenbacker sound. What enticed you about those guitars and their unique tones?

A lot of the music I grew up with and was inspired by -- from the Byrds to the Beatles to the Rolling Stones -- was played on Rickenbackers. Probably the first person I ever saw playing one was John Lennon, and I always loved his sound. But I think what really turned my head around was hearing the Byrds on the radio. That sweet, ringing, melancholy sound of the Rickenbacker 12-string really touched me, and I've always sought that sound and tried to incorporate it into whatever I was doing.

Do you consciously try to use different guitars and amps for every song?

We could make a whole record with one Stratocaster and one amp if we wanted to, but there are so many beautiful instruments and different timbres that you can explore. It's also fun to try to make other kinds of sounds so you don't get bored with the same thing. The way we use our instruments is often very spontaneous. For example, last Christmas my wife gave me a '60s Vox 6-string with a built-in fuzztone. I took it right over to Jeff's studio, and it turned out to be perfect for a new song that Tom had brought in.

Tom talks about a certain sound that occurs when both of you are playing. Do you do anything in particular to complement what he plays?

Most of the time, Tom is playing and singing at the same time, and because his rhythm is so solid, I don't always need to reinforce it. Often, I'll try to find a counter rhythm that is complementary. Then, between the holes in his vocals where he's just strumming, I might try to play something -- like a lick or a melody of some kind of sound -- that will continue the character of what he's singing. Occasionally, I'll double what he's doing just to thicken it up, but, generally, I try to play parts that will make the whole thing sound wider.

Do the songs evolve as you start playing them live?

It depends. There are certain songs where the record version is really the only way to put it across. If you start tampering with it -- or try to overdevelop certain aspects of it -- you will distract from the pure heart of the song. But there are songs that we might want to stretch out on, or perhaps break down in the middle in order to get the audience involved. On something like "American Girl," though, there's something so special about the way the record worked, and we try to recreate that as closely as possible, because that's where the soul is.

How do you approach working out a solo?

I'd say that 95 percent of my solos are spontaneous, but, again, it depends on the song. If the band is tracking live, we'll tend to be pretty spontaneous. On "Runnin' Down a Dream," which has that long solo at the end, I think we did three takes, and just took the best bits and stuck them together. If it's a song that's built up part-by-part, and we want to overdub the solo, it will usually come near the end of the finished record. In that case, I have plenty of time to really listen to the song and hear all the little tonalities and spaces and things. I also listen really closely to the melody Tom is singing, and if I get stuck, I will sometimes start out just playing that exact melody on the guitar. That's a good little trick to ensure that what you're playing fits the song.

You don't use much distortion, but your tones always have a nice singing quality. What's the secret?

Each amp has a sweet spot between where it sounds dinky, and where it starts to get a little crappy. So I tend to set the tone controls relatively flat, and just bring the volume up until I find that sweet spot. The rest of it is just up to your hands and your playing. Generally, we don't distort too many things on our records. If you listen to the Beatles, or Elvis, or early Rolling Stones records, the distortion you hear is very natural. It's a little bit of the amp, and maybe some overdrive from an overloaded microphone preamp. I like to hear the clarity of the notes and those bell tones. When your guitar sound is too distorted, you lose all of that, and the tone becomes more of a honk.

You also don't seem to have any hang-ups about using solid-state amps.

We've gotten to a point where we've realized we can get better sound if we keep the overall stage level quieter. So what I've been using on the last couple of tours is just a Fender Princeton positioned up in front of the stage and facing me. Behind me, I have a Fender Deluxe and my old Vox AC30 -- which are facing out from the side of the stage. I feel those amps more than I hear them, but our soundman can bring up the three amps in the house mix and blend them at his discretion. Mostly what I hear on the stage, though, is the Princeton.

In looking back on your 30 years with the Heartbreakers, what have been some of your most satisfying moments?

Probably the biggest one was when we cracked the egg on Damn the Torpedoes. That's when we broke through, and went from being a medium band to a major band in terms of how many records and tickets we could sell. With Torpedoes, we hit a commercial peak with a couple of big songs, as well as the audio production quality that lifted us up to another level. But there have been lots of other peaks, too. I love the first album, because that's when we found our sound and established who we were. Working with Jeff Lynne on Full Moon Fever opened up a whole new world of recording with a really special group of songs. And working with Rick Rubin was a peak, because he got us back to playing live in the studio again.

One of the greats you've had the opportunity to play with was George Harrison -- can you share any of that experience?

Well, I was mostly just amazed that he would take the time to sit down and play guitar with me. The first time we played together, I had some old bluegrass-finger-picking thing, and I said, "Do you know this song?" I expected him to get up and walk out of the room, but he goes, "Oh, I can play along with that." And so it was just the two of us trading licks, and it struck me that here's this guy who is a hero of mine, but he's also just a guy who loves the guitar as much as I do. George was a very gracious person, and he always brought little gifts -- like hats and Beatles watches -- when he came to visit. I loved his humor. I remember telling him once how much I admired his sound with the Beatles, and he said, "Oh, we had those Gretsches. If only we'd had Strats, we could have been really good!"