Tom Petty's Last Dance

By Neil Strauss

Rolling Stone #1004 - July 13, 2006

Celebrating three decades of work -- and his first album in four years -- Petty says that this summer's tour with the Heartbreakers may be the final go-around

It is a high-security situation at the Sony Studios lot. Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers are in Los Angeles winding up their penultimate rehearsal for what Petty says will be the band's last all-out tour. And the only outsider they've allowed in is the legendary director Peter Bogdanovich and his crew, who have been recording the band's every breath for a forthcoming documentary. Each song Petty plays -- from old Fleetwood Mac covers to his new ballad "Square One" -- elicits a flurry of excitement from Bogdanovich, who instantly starts asking what song it is, comparing it to earlier rehearsals and figuring out what camera coverage he has on it.

When the rehearsal ends, Petty looks around the studio, lost and out of place, until his eyes fix on his free-spirited blond wife, Dana. She presses against him, his face fills with life, and the two merge into one self-contained suede-fringed being for the rest of the evening.

And that is when his new solo CD, Highway Companion, snaps into focus. It is Petty's first new solo album in twelve years, and it has been four years since he has released an album with the Heartbreakers, who are celebrating thirty years together.

Nearly all the characters on Highway Companion are on the run -- by land, sea and air. But unlike a Bruce Springsteen album, where the open road represents freedom from the dream-crushing traps and responsibilities of growing older, Petty, 55, catches up with these characters years later, when they're disillusioned by this freedom. As he sings on the new album, "Living free is gaining on me." The characters are bored and lonely, adrift in nothingness, yearning to return to the anchors of home, family and love, but not even knowing if they're still waiting for them or not.

In his own life, Petty finally seems to have set anchor after a long drift. The turn of the century was not kind to him. In the late Nineties, he separated from his longtime wife and disappeared hermitlike into a chicken shack, where many of his friends worried he was doing heroin. In that time, he battled clinical depression and released one of his worst-performing albums, Echo. He bounced back in 2001, moving to Malibu and marrying Dana York. His 2002 album The Last DJ, a rock-opera condemnation of the state of the music business, did little to ingratiate himself with the cultural gatekeepers he has spent most of his career fighting (in 1981, he went to war with MCA over the label's plans to issue the follow-up to Damn the Torpedoes for $9.98, a dollar above the then-standard list price, and won -- he celebrated on the cover of ROLLING STONE with a shot of him tearing a dollar in half). And in 2003, Heartbreakers bassist Howie Epstein, who had been fired from the band a year earlier, died of a heroin overdose.

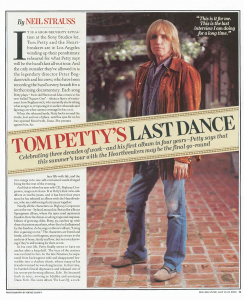

A few days after the rehearsal, Petty sits in his Malibu home on a warm summer afternoon, wearing his ever-present brown suede-fringed jacket and matching moccasins with black socks. Though from a distance he looks like he hasn't changed in a quarter of a century, up close his face displays the deep lines of experience. Only his pale-blue eyes (which rarely make direct contact with the person sitting opposite) and his sporadic guilty smile betray a childish energy. Every few minutes, he arches his back like a cat, extends his arms into the air as far as they will go and stretches his bones. He then freezes in that position for several awkward seconds, occasionally dropping his cigarette to the floor.

Often the best interviews are given by the musicians who avoid them the most, like Bruce Springsteen or Eric Clapton. And often one of the reasons they don't like to sit down for an interview is because they are too honest and sincere in these types of interactions, unwilling to go into autopilot and parrot the same answers they've given before. This is true of Petty, who keeps extended the interview well past its appointed deadline.

"This is it for me," Petty says as he takes a sip from a mug of old, cold coffee. "This is the last interview I am doing in a long time."

These are strange words coming from Petty, because he's done hardly any interviews in the past year. And the CD that he is supposed to be promoting not only hasn't been released yet, he hasn't finished mastering it or sequencing it. In fact, though the record is coming out on July 25th, when we speak in early June he hasn't even turned it in to his label yet.

But Petty is not like other artists. When asked if he'd prefer instead to disappear from the public eye like legendary recluses Sly Stone or Captain Beefheart, he goes silent for a moment, then nods his head softly. "Yeah," he admits. "I can see myself that way very easily."

This is the longest amount of time that's ever elapsed between albums for you. What took so long?

You know, that didn't occur to me until recently. I don't know if I was just fed up with it all or what, but I didn't really feel compelled to run out and do another record. I thought, "I am going to take my time." Then someone told me the other day that it's been three years.

It's actually been four years.

Has it been? Four years? That's a long time. I am surprised that I waited that long. But I honestly didn't even notice the time going by. And it didn't take long to make the record, just a few months. I guess I was touring and I took my time writing.

The songs on the album all seem to have similar themes about drifting lost in the world and looking for something solid to hold on to.

What is that wrong? It's got the line "It's hard to say who you are these days, but you run on anyway, don't you?" ["Saving Grace"] And that's kind of how I see these times. There are a lot of people who aren't sure who they are anymore, so they're just trying to keep their head above water because things are moving really fast these days. There is a lot of information flying around and a lot of people staring into their palms. [Pause] I don't know why I took so long [to make this album]. That really staggers me that it took so long.

It seems you have made a comfortable life for yourself with your family in Malibu, but when I heard the record, I heard loneliness. Where does that come from?

It wouldn't have been a very good record if I just sat back and wrote about how happy I was. But I am pretty happy these days. I've gone through the dark tunnel and come out the other end in a lot of ways. I have a good family, my kids are doing well, and I have a young boy who just turned thirteen, and that's a whole movie on its own. I never really had any real family. My mom died when I was quite young, and my dad was never around much. And so when I married Dana, she and her mom and her brother lived down here, and they kind of adopted me into their family. Actually, her mom is one of my main assistants. She runs the whole estate. So I feel good having that kind of bond with a family.

I remember just before you moved out here, people were worried about you because you had split up with your wife and were living in a shack somewhere.

Yeah, I was living in a pretty rundown shack. I didn't mind it. It was in a part of the Pacific Palisades, in the woods. And I was living back there and had chickens and all kinds of shit. In some places, you could actually see the daylight coming through the walls of the cabin. But it was my bachelor pad, you know. I had a big adjustment to make, and maybe they were right to be worried about me. I had a lot of free time in that period, and it wasn't the best period in my life. But I am through that. I came out the good side.

What was the wake-up call that made you clean up?

Oh yeah, well, you know, it was "One of us is dead." It's like, "Shit." Yeah, that's a big wake-up call. I've lived life pretty hard, I took an adult portion of life and squeezed it into a very short around of time when I was younger. We lived hard, we didn't sleep much, we traveled all the time. In this job, you don't realize that you're getting older. Then probably around the time I got married again, I said, "I am going to try and act my age now." I am still coming to terms with it a little bit, but it's not bad.

The thing that's tough about it is you realize you have a limited amount of time left. That's the first time that ever dawned on me: "Oh, shit, you're going to run out of time." That's one of the reasons I don't want to spend the rest of my life touring -- I have done it. You can do that and then look up one day, and a lot of your life has gone by, and all you did was go around doing rock & roll shows.

Doesn't it get scary when you start counting your years backward instead of forward?

Yeah, and you realize this music is going to be here a long time after I am gone. So I want to really put everything I can into it and make it as good as I can and get everything in me out.

Do you feel that there are things that you haven't gotten credit for as an artist?

As successful as [the Heartbreakers] have been, part of me thinks we have also been taken for granted to a degree. Maybe that's because we have always been consistent. We don't really make bad records, though some people might like some more than others. And we have never really done a bad show. So I think in a way maybe we've been taken for granted.

I think maybe if we were gone, God forbid, there would be a different take on us. Because this group is really the last link to that whole California thing -- to the Byrds, Buffalo Springfield and that whole era of music that came along. This is probably the last thing that attaches to that.

Was it hard to recover from losing Howie Epstein?

The band has a good family atmosphere that wasn't there for a while. It came back about a year or two ago. I think when [bassist] Ron Blair returned, it really bonded us back together in a weird way. If he hadn't been there, I am sure it would have been the end of the whole thing when Howie died. It was kind of cosmic, in a way, Had we looked into putting a new person in the Heartbreakers, I would have just walked away. It wouldn't have been a band to me. I think we all knew that this is the end of it. And Ron stepped in and had this huge enthusiasm through the whole thing. When he first quit, he didn't quit the band, he quit the whole music thing. He was fed up. But we were all young boys then. When he got interested in music again, he started playing with Mike [Campbell, Heartbreakers guitarist and producer] quite a bit, and so he was just there when we needed a bass player for the last two tracks we did for The Last DJ.

Are there any plans for a new Heartbreakers record?

I have got a lot of music, I tell you. I have a good sixty percent of a Heartbreakers record just sitting there waiting to be finished. I feel pretty musical at the moment. That's why I want to stop going on the road for a while after this, because I want to get all these projects done. Time is precious these days.

What are the other projects?

The Heartbreakers one is going to be a big one. We also have a live album we have been threatening to do for years, and Mike Campbell is actually producing that. So I think that will probably come out a year from now. And then, beyond that, I want to reform Mudcrutch [his original Seventies band before the Heartbreakers] and do a record with them. That would be fun, more of a country-rock kind of thing, which is where we came from. But whether I can convince them all to do it or not, that is the question.

Which of the guys do you think would be reluctant?

I think it's just a matter of personalities. Like Randall Marsh, the drummer, would be essential to it. But I haven't seen him in years. I did play with him probably four or five years ago at Mike's studio. And he's a really good drummer. But I talked to Mike about him, and he was like, "I don't really get along with him." And it was right as I was about to say, "Why don't we do the Mudcrutch thing?" So I decided not to bring it up right then [laughs].

Have you heard the Red Hot Chili Peppers song "Dani California" yet, because obviously it sounds a lot like "Mary Jane's Last Dance."

Yes, I have. Everyone everywhere is stopping me. The truth is, I seriously doubt there is any negative intent there. And a lot of rock & roll songs sound alike. Ask Chuck Berry. The Strokes took "American Girl" [for their song "Last Nite"], and I saw an interview with them where they actually admitted it. That made me laugh out loud, I was like, "OK, good for you." It doesn't bother me.

There have been news reports that you were going to sue the Chili Peppers.

If someone took my song note for note and stole it maliciously, then maybe. But I don't believe in lawsuits much. I think there are enough frivolous lawsuits in this country without people fighting over pop songs.

How did you end up getting back together with former Traveling Wilburys bandmate Jeff Lynne to produce "Highway Companion"?

Olivia Harrison asked me and Jeff if we would induct George Harrison into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame [in 2004]. And Jeff doesn't perform live ever, which I don't understand, because he's really good at it. So it took a little bit of arm-bending to convince him to play. The show went great, and then we were coming back on the plane and we said, "Look, let's get together and cut a track." That's how it always begins -- with "a track." So we got a track, and then it went so good that I just said, "We're pitching tent here."

And what made you decide that this was going to be a solo album and not a Heartbreakers record?

Well, they weren't there. We started on the Christmas holiday, and I just wanted the three of us [Lynne, Petty and Campbell] to make a solo record. I probably hurt Benmont [Tench]'s feelings, but I think the world of Benmont. He is really the best piano player there is anywhere. I just thought for this record, I'd rather bang it out myself and make a different kind of record. And I am really proud of this record. I think it's one of my better ones in a long time.

"Square One" stands among your most beautiful songs.

Thank you. I think it's one of my best songs ever. I mean, you always like your new record. But I think that one is particularly good.

Did you record it in the studio in the other room here at your house?

There used to be a studio there. But right now they got it all packed up, because we have termites in the walls. So they just emptied everything out and covered the wall with plastic, and they were going to blast this place with insecticides. Of course, out of the whole home, the only room to have termites would be the studio.

You're probably in an interesting relationship with the record right now because you're in the middle of it. When you hear it, what do you feel?

I finished a lot of this a long time ago. I went away from it for a long time. I didn't want to wear myself out on it. So when I came back to it, I was really pleasantly surprised.

How long is a long time?

A year. I went on the road. I did one more track ["Saving Grace"] when I came back, and then I started listening again. I haven't given it to them out of sequence. I set out not to make a theme-oriented album, because I did that last time. But when I sat back and looked at it, there were themes creeping into it.

I always wanted to ask you if Ray Davies was a big influence on the songwriting on "The Last DJ."

Very much. I love Ray Davies. I especially liked that Lola Versus Powerman album, and I felt it was time for an album with those themes again.

Did you get much of a backlash from the music industry since the release of the album?

Yes.

In what ways?

In every way possible. I got a lot of criticism. But I saw the record more as a sort of moral play rather than a specifically music-business-oriented thing. Bob Dylan told me that he actually liked the record a lot. He said I shouldn't confuse things that are popular with things that are really good. That was the best review I got.

You did a lot of fighting to keep record prices down. Do you feel in the end it had any effect on the music industry?

Certainly I am glad I did it. I tell you, it really beat me up. My psyche suffered. I felt like I had the shit beat out of me. Because [obstacles] came at me one on top of the other, and no other artist stepped forward to say, "Yeah, me too." Nobody.

But I know I held the prices down for a long time. I know that was directly my doing. But I also knew that eventually I was losing the battle. It's interesting that that's what sank the ship, in a way. I think that if they kept the CDs really affordable, there wouldn't have been the tragic impact from the computers that there was. And that's a blow that I don't think they're ever going to recover from.

Well, services like the iTunes Music Store are helping restore the balance.

iTunes is a great idea. It reminds me of the old days when you bought a single for ninety-nine cents, and if you liked that, you bought the album. But it's not as good for selling or even acclimating people to the album as an art form. I was up until the middle of the night sequencing this thing. And I am starting to think, "Who cares? 'Cause they're just a bunch of button pushers." But I am not giving up my art. I make complete pieces of work, I like to think.

Do you think the concept of selling out has changed in the past decade because the orders between what's art and what's corporate aren't so clear anymore?

Selling out is a funny concept, because we are in a business that is all about selling. I have turned down a lot of money for things that would have made me feel cheesy. And I think I made some of those moves when I couldn't afford it. But I think I'd feel really bad seeing "American Girl" selling gas or Chevy trucks. The song means more to me than that.

But now there are some young groups coming up who really want to get a commercial because the radio has become a different animal where you can't really get airplay for a new group, or any group, really. So maybe they think that's their only road out. I am so glad I missed that and didn't have to make those decisions.

What label did you finally decide to put your record out on?

It's coming out on American. That's another reason why the record is taking so long. My contract was up, and a lot of labels were bidding against each other. I ended up staying with Warner, but then they gave me the choice to do with Reprise, Warner or American. And of course I went to American, because Rick [Rubin, who runs the label and has produced Petty] is an old friend, and I trust Rick.

The music business has changed so much. I know enough to protect myself, but that's about it. I don't really know how it works anymore. For the last four months, there have been more demands on my time than I can remember: the press, this [Bogdanovich] movie, the tour coming up, then a radio show [on XM], King of the Hill [where he's the voice of Lucky]. You have to fight to just get a few hours. It's gotten where everything has gotten so media-oriented.

It's almost like when you make a record, you got to be punished for it.

Between the Internet, satellite, radio and satellite television, there are way too many media and promotional outlets now.

It's more than I am going to deal with, I'll tell you that. I am straight up. This is the last interview I am doing, because I have to live life. I can't spend every day fulfilling the needs of the label or the media in order to promote the record. I love the record and I really care about it, but there is a point where you start to not like yourself [laughs].

I have tried to explain this to the label. My mind is so delicate, and I am sure it comes from the life I have lived. But my mind is so delicate that I can't take being part of that. It's just like hanging around after a show to meet people. I can't do that. I don't even do interviews on the road.

So I am not the best star for promoting himself. I think that's the whole problem with out career. For someone of the stature that we are, we have never embraced the promotion machine. Maybe we should have.

If you'd embraced it, you may have been even bigger, but you'd be much less happy.

I say if things were any bigger, I couldn't deal with it. If I was more famous or more successful, it would be too much.

Petty's Deep Cuts

If you only know the greatest hits, you don't know how remarkable Petty can be. Here are ten of his best songs that haven't been in heavy rotation

Casa Dega

B Side of "Don't Do Me Like That"

Cut during a flurry of activity that yielded "Refugee" and "Here Comes My Girl," this gem was criminally relegated to a B side. Over the years it's become a fan favorite.

Shadow of a Doubt

Damn the Torpedoes

A tender solo acoustic version of this Damn the Torpedoes cut, from the Bridge School Concerts compilation CD, brings all its yearning straight to the surface.

Waiting for Tonight

Playback

The Bangles sing backup on this jangly outtake, cut for Full Moon Fever while producer Jeff Lynne was away in England.

Finding Out

Long After Dark

Bassist Howie Epstein reveals his great vocal chops as he harmonizes with Petty on this tale of a relationship imploding.

A Thing About You

Hard Promises

This organ-heavy New Wave tune was a highlight of the follow-up to Damn the Torpedoes.

Don't Fade On Me

Wildflowers

Just voice and twin acoustic guitars, this is one of Petty's simplest and prettiest cuts.

Room At The Top

Echo

Kicking off his post-divorce album, this ode to the solitary life begins with quiet piano before the band kicks in hard.

You Got It

Roy Orbison

Petty and Jeff Lynne helped Orbison write his brilliant comeback hit, though Orbison wouldn't live to see it climb the charts.

Blue Sunday

The Last DJ

Petty has called this moving tale of a depressed hitchhiker who befriends a stranger at a 7-Eleven a "little short movie."

Dreamville

The Last DJ

Strings back Petty on this look back at the music of his childhood. As personal and sentimental as the man's ever gotten.

Download Now: Must Have

By Andy Greene

Rolling Stone #1004 -- July 13, 2006

Tom Petty, "Saving Grace" | All major services

The first single from a great year for Petty

In 1980, in the wake of a devastating divorce, Bob Dylan released a song called "Saving Grace," which outlined how his evangelical convictions offered him salvation. Twenty-six years later, Tom Petty is coming off a similar situation -- in recent years. he's dealt with both the death of a bandmate and a divorce -- and he's also got a tune called "Saving Grace" (from his upcoming album Highway Companion). Unlike his mentor, though, Petty finds the answers inside himself. He also wrote a much better song.

Utilizing a shameless Bo Diddley "Who Do You Love?" beat (considering how much the Strokes and the Chili Peppers have ripped Petty off, he's earned the right), Petty sings, "It's hard to say who you are these days/But you run on, anyway/Don't you, baby?" If the rest of Highway Companion is this strong, Petty might just be entering his Time Out of Mind period.