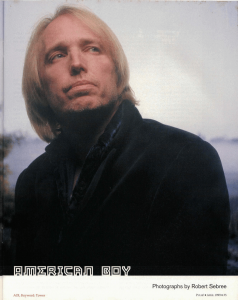

American Boy

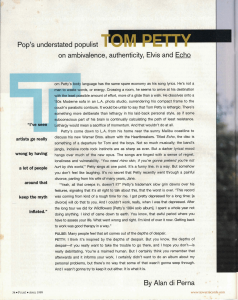

By Alan di Perna

Pulse! - April 1999

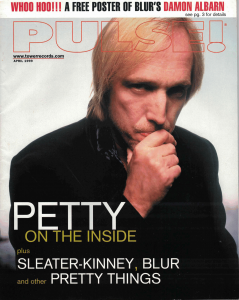

Pop's understated populist Tom Petty on ambivalence, authenticity, Elvis, and Echo

Tom Petty's body language has the same spare economy as his song lyrics. He's not a man to waste words, or energy. Crossing a room, he seems to arrive at his destination with the least possible amount of effort, more of a glide than a walk. He dissolves onto a '50s Moderne sofa in L.A. photo studio, surrendering his compact frame to the couch's parabolic contours. It would be unfair to say that Tom Petty is lethargic. There's something more deliberate than lethargy in his laid-back personal style, as if some subconscious part of his brain is continually calculating the path of least resistance. Lethargy would mean a sacrifice of momentum. And that wouldn't do at all.

Petty's come down to L.A. from his home near the sunny Malibu coastline to discuss his new Warner Bros. album with the Heartbreakers. Titled Echo, the disc is something of a departure for Tom and the boys. Not so much musically; the band's jangly, incisive roots rocks instincts are as sharp as ever. But a darker lyrical mood hangs over much of the new opus. The songs are tinged with a sense of regret, loneliness and vulnerability. "You need rhino skin, if you're gonna pretend you're not hurt by this world," Petty sings at one point. It's a funny line, in a way. But somehow you don't feel like laughing. It's no secret that Petty recently went through a painful divorce, parting from his wife of many years, Jane.

"Yeah, all that creeps in, doesn't it?" Petty's trademark slow grin dawns over his features, signalling that it's all right to talk about this, that the worst is over. "This record was coming from kind of a rough time for me. I got pretty depressed for a long time; [a divorce] will do that to you. And I couldn't work, really, when I was that depressed. After the long tour we did for Wildflowers [Petty's 1994 solo album], I spent a whole year not doing anything. I kind of came down to earth. You know, that awful period where you have to assess your life. What went wrong and right. I'm kind of over it now. Getting back to work was good therapy in a way."

PULSE!: Many people feel that art comes out of the depths of despair.

PETTY: I think it's inspired by the depths of despair. But you know, the depths of despair—if you really want to take the trouble to go there, and I hope you don't—is really debiliating. You're a maimed human. But I certainly think you remember that afterwards and it informs you work. I certainly didn't want to do an album about my personal problems, but there's no way that some of that wasn't gonna seep through. And I wasn't gonna try to keep it out either. It is what it is.

PULSE!: Is it a function of artistic maturity too—the fact that you're able to be less guarded in your lyrics?

PETTY: Yeah, you do get less guarded, because you want the song so badly. I'm so glad when a song shows up that I really embrace it. I don't question it much. I don't do nearly as much rewriting and proofing as I used to do. Unless something's really terrible, I let the song lay there just the way it came in. I don't labor anymore. I don't think you're supposed to at my stage of life. I think I've really honed what I do. If I sit and wear over a song these days, I usually don't get a good result. It feels overworked.

Despite its dark overtones, Echo isn't really a depressing album. The mood is more one of triumph over adversity—a feeling that's driven home by the Heartbreakers' powerhouse playing. Coming off a critically-acclaimed, 20-night residence at the Fillmore West, the group was in top form when it entered the studio to cut Echo. Petty's longtime band has been a part of everything he does, including his two solo albums (1989's Full Moon Fever and the aforementioned Wildflowers) and the 1996 film score She's the One. But there hasn't been a full blown Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers album since 1991's Into the Great Wide Open. Petty felt the time was long overdue.

"I really wanted to make this an album with the band," he says. "It's been so long since we really came together under that heading, where everybody took an equal interest in the record and worked really hard. No matter what I'm recording, I always bring the Heartbreakers in, in some fashion or another. But the difference in this album, more than their playing, is their input. Mike [Campbell, Heartbreakers guitarist and longtime Petty co-producer] was the engineer on this album. So when we tracked, 90 percent of the time there was no one in the studio but the musicians. We tried to arrange the music so there were very few overdubs. Ben [i.e. keyboardist Benmont Tench] played three keyboards at a time and Mike did a lot of the guitar solos live when they came up. Then in the end, Rick Rubin [Petty's co-producer since Wildflowers] came in to help us finish. We'd recorded way too many songs and didn't know how to cut it down."

Petty has been playing with Campbell and Tench since his teen years. Bassist Howie Epstein joined in 1982. "Auxiliary" Heartbreakers Steve Ferrone (drums) and Scott Thurston (guitar) have been around longer than permanent members of many other bands. Beyond their first-rate musicianship, the Heartbreakers are incredibly adept and tuned-in interpreters of Petty's songwriting.

"It's a little scary," he says. "I'll show them a new song and 20 minutes later, it's done. And they're saying, 'OK, what else you got?' There's a song on the new album called 'Swingin'' that was written right on the spot. I was sitting with the band and we were supposed to be doing another song. I just came up with this new song and they followed me. I called out the chords and ad-libbed the words. They said, 'We oughta do this for the record.' I said 'Really? OK.' We played it again with the tape rolling, and that was it."

The song ends with a series of ad-libs name-checking pop culture icons who "went down swingin'"—from Benny Goodman to Sonny Liston. Petty drops legendary names elsewhere on that album, which helps give Echo a broad, almost mythic scope that transcends the purely personal. Abraham and Isaac turn up, drunk and disorderly, in the carnivalesque "About to Give Out"—just two more loners adrift in a universe parallel with Dylan's Highway 61. Davy Crockett and Roy Rogers come along for the ride, too.

"Yeah, there's a whole bunch of mythic people in this album," Petty allows. "And I don't know why. They just appeared."

PULSE!: Billy the Kid is in there, too.

PETTY: Billy the Kid's another one. Why is that?

PULSE! I was hoping you'd tell me.

PETTY: I don't know. They just appeared.

Like his good friend Bob Dylan, Petty doesn't like explaining his lyrics: "I'm not one of those people who says 'I just wrote a song about this or that subject.' Usually, when somebody says that, it's a bad song. I'm really wary of anyone that discusses their writing with me or tells me they wrote about this or that. That should be apparent when I hear the song, rather than them trying to help me out."

Petty's lyrics have a Zen-like economy that doesn't really lend itself to a prose gloss. He's a master of laconic lines that place emotional resonance over concrete significance, whether they take the form of heavily repeated mantras ("Free Fallin'," "Don't Come Around Here No More") or cryptic koans ("I'm learning to fly, but I don't have wings/Comin' down is the hardest thing"). Like Bruce Springsteen, Petty's a great populist. But where Springsteen uses bombast, Petty uses understatement. His lines are generously supplied with openings that invite listeners to try them on and apply them to their own life situations. Even his narrative songs are filled with areas of indeterminacy—gaps into which the listener can read himself or herself.

"Yeah, I'm real good with ambiguity," he says with a grin. "You've only got four minutes or so in a song. If you nail things down too mich, it doesn't seem to hold up to repeated listenings. You wear out on it quicker if you get a narrative and you stay with the storyline real close. Although there are some exceptions. Like [the traditional folk song] 'Long Black Veil' is pretty narrative and pretty great. But there's still imagery in 'Long Black Veil.' There are still ends you don't completely understand. But then again, you don't want it to be so ambigious that it means nothing to no one."

Interestingly, many of Petty's best and most well-known songs are about female characters—from "American Girl" to "Mary Jane's Last Dance." The archetypal Petty character is a small town girl who feels trapped by her surroundings and yearns for something grander. "I always just thought that was really romantic, when I was younger," Petty says of this recurring theme in his work. "I've always loved girls. And I found they were interesting characters to write about, maybe more so than men. It's easier, for me, to write about female characters. It just comes to me easier. And when the Heartbreakers were starting out, you didn't hear many positive songs about girls. There were a lot of songs about girls, but a lot of times they kind of put them down. They didn't come off too strong. And somewhere along the line, on the first or second album, I started to write songs that kind of gave them a positive image. I still enjoy doing that. Although I got a little tired of the theme. I don't know why it keeps coming back. It does, though."

PULSE!: Much contemporary ideology says that only women can write sympathetically about women.

PETTY: Sometimes I think they don't write as well as men do about women. You get women all hung up on women—it's really boring. I mean I sympathize with them and all that. But I just think it's really boring when you get women all revved up about women. It's probably the same when you get men all revved up about men.

PULSE!: You get Robert Bly: the men's movement.

PETTY: That's boring too. It's probably good for us to observe each other, the sexes, the comment. It's probably more interesting coming from the other side.

Gender differences aside, there's something autobiographical in those songs about small town misfits itching to bust out. "I certainly felt that way as a kid growing up in a small town," says Petty of his childhood in Gainesville, Fla. "I discovered the limitations of the place early on, because of TV. There was so much information coming in all of a sudden. On TV, there was all kinds of stuff going on, but not in Gainesville. There's a lot of nice things about the town I grew up in. But I wasn't the kind of person who would have been content to settle and stay there. There's nothing wrong with that. Sometimes I wish I was that kind of person."

Petty's love affair with rock'n'roll began when he was a preteen. It was triggered by a personal encounter with none other than Elvis Presley, who came to Gainesville in 1962 to shoot some scenes for his film Follow That Dream. Petty was among the crowd of onlookers. From that day forward he was hooked.

"Elvis really did mean a lot to me as a child," says Petty. "The whole idea that this person came from poverty like me, and he got out and made something of himself. And that he did it by doing something pretty cool, rather than something that was devious, or being a crooked politican or any of the normal Southern ways out of things."

The Beatles' arrival inspired Petty's first efforts at guitar playing and songwriting. He later joined forces with Tench and Campbell to form Mudcrutch, an early incarnation of the Heartbreakers. Mudcrutch landed in L.A. in the early '70s, eager to take their shot at stardom. Their one and only single, "Depot Street," was a flop, but Petty found a niche for himself in the L.A. music community as an apprentice songwriter working under producer Denny Cordell and artist/producer/tunesmith Leon Russell. L.A. also provided an education in record biz pitfalls.

"We really saw all the bullshit firsthand," Petty recalls. "Groups that show up and ride around in limos on their first album, and have huge industry parties. And they're terrible and everybody knows nothing's gonna happen. Everybody but them. And we saw people that got sold on the gimmick: 'If y'all dress up this way and do that...' We knew not to do it. Like, 'I'm not getting in any suit of clothes. I'm not joining anybody's club. We're just gonna do our thing.'"

This didn't stop Petty and the Heartbreakers from being lumped in with the punk/new wave scene shortly after the release of their self-titled debut album in 1976. Like many new wavers, Petty and his band were drawing inspiration from the mid-'60s golden era of bands like the Byrds and Animals. So there was some common ground, although Petty never held much truck with new wave's elitist tendencies. The love affair lasted until 1979, when the Heartbreakers' third album, Damn the Torpedoes, went multiplatinum and hits like "Refugee" and "Don't Do Me Like That" became mainstream radio staples.

"It was unusual being lumped in [with the new wave]," says Petty. "But it felt better than being lumped in with the other side! We agreed with them in spirit. Music had gotten really bad in our view, and we hated seeing stuff we believed in watered down and crassly commercialized. But we never thought we were [new wave]. And we never tried to embrace it. But it felt pretty cool to be alternative, you know? And it kind of hurt when we got really popular and it felt like, 'They see us as rich people now.' But really, we hadn't changed."

Los Angeles provided Petty not only with his early music biz education, but also with the subject matter and setting for some of his best songs, from "Free Fallin'" to "California." Like most Angelenos, he's suffered his share of natural disasters, including a fire that destroyed his home and came close to costing him his life in 1987. But also like many Angelenos, this hasn't kept him from a passionate attachment to the city.

"There's something really magical about it," he says. "It just feels like all the people who want to escape their little small town hells and really don't fit into conventional life had for Los Angeles. That's good and bad, but it's endlessly entertaining. And L.A. is a consumer's paradise. If you're a Grade A consumer like me, it's amazing. Right now I kinda want to get away from writing about it, though. I feel I've covered L.A. But I do love Southern California and Los Angeles. It's always been the land of milk and honey to me."

A few years ago, Petty moved a little ways out of town, to the Malibu beach community of Point Dume. And he spends time visiting his two daughters who've moved to New York. ("They think it's much hipper, although they miss driving," he says.) His golden L.A. period was really the mid-'80s when he was living south of Ventura Boulevard in Encino, in L.A.'s suburban San Fernando Valley, just around the corner from the Eurythmics' Dave Stewart who co-produced Petty's '85 Southern Accents album and its sitar-tinged, ornately orchestrated mega-hit "Don't Come Around Here No More."

"At that time the Heartbreakers were looking for something new," Petty says. "We felt like we'd taken the Big Jangle as far as we could. I liked Dave because he just had no reverence for anything, which helped me shake out of what I was doing and go somewhere else."

Petty has never lacked for gifted friends. Early in his career, he was befriended by former Byrds mainman Roger McGuinn, who'd heard Petty's "American Girl" on the radio and thought it was some song of his own that he'd forgotten about. McGuinn wasn't the only one of Petty's musical heroes with whom he'd get to collaborate. He had known Bob Dylan since the late '70s, but the two artists drew closer when the Heartbreakers began touring with Dylan as his backing band in 1986.

"I think I really understood what Bob wanted to do at the time, and I got off on it a lot," Petty says. "Like, 'Hey, we're Bob Dylan's band and we're gonna lay it down tonight.'"

George Harrison is someone Petty first met shortly after he landed in L.A. in the mid-'70s. "But we weren't really buddies until the middle and late '80s," says Petty, "when I started working with Bob. Then George started to come around." The next thing anyone knew, along came the Traveling Wilburys, a band of itinerant siblings—or were they supposed to be cousins?—who bore a striking resemblance to Petty, Dylan, Harrison, former ELO member and über-producer Jeff Lynne and—for the first Wilbirys album, anyway—the late, great pop singer Roy Orbison. For Petty, the youngest member of the group and one who grew up idolizing the others—particularly Dylan and Harrison—it must have been rock'n'roll heaven.

"Well, they treated me equally, which was nice," he says with a grin. "But I always felt like I was the kid in the band. I was the one who was really lucky to be there. But they never treated me that way. I actually just spoke to George this morning about doing the Wilburys again. We'd all still like to do stuff. I probably say that in every interview I do, but it may still happen. Maybe next year. 'Cause I got a tour to do until October."

Harrison has become a particularly close friend and regular guitar budy. His influence can be heard on Petty tunes like "Into the Great Wide Open" and "Hope You Never." "Me and George and something somewhere where we're connected," Petty says with a laugh. "Some past life or something. I don't understand it."

Jeff Lynne also became a presence in Petty's music, producing Full Moon Fever and Into the Great Wide Open. In 1994, Lynne was succeeded by American Records chief Rick Rubin, who acted as Petty's co-producer for Wildflowers and the soundtrack album She's the One before lending a hand on Echo. Petty has mixed feelings about his one and only soundtrack project. He admires director Ed Burns and wrote a couple of tunes for She's the One. But trouble began when he found out he was also expected to call up other artists and ask them to contribute songs to the picture's soundtrack album.

"I started to do it," he says, "and I realized, 'This is a bad thing.' Because, first of all, I know these people don't want to give anything good. Who wants to give their best stuff away, right? And those albums just really suck, every fucking one of them. I never wanted my songs on an album next to somebody's music that I didn't respect. So I just took a bunch of stuff that I had left over from Wildflowers and I hastily did a couple more tracks. I just ended up doing everything on the album myself."

For Petty, the multi-artist soundtrack album is emblematic of what's wrong with the current music scene, in which one-shot disposability has come to reign supreme over long-term artist development: "You have a whole young audience out there that feels everyone is completely disposable who wasn't around in the '70s. Like if you didn't make icon status by the early '80s, nobody's gonna care. [laughs] The attitude among the record companies seems to be, 'We have enough icons now and we're just gonna dispose of everybody else track by track.' And the soundtrack thing really plays into that. Never mind developing bands and making them have an air of quality about them. Nah, just put a bunch of stuff out there and see what sticks. I think it's a really scary time in pop music. Because the farm teams aren't there. Down the line, I don't see anybody breeding too much. I always could in the past."

Of the current "No Depression" bands laying claim to the American roots rock mantle of authenticity, Petty gives thumbs up to Wilco. "I caught on to Wilco way back," he says. "That guy Jeff Tweedy, he's really good. He's gonna do stuff and be around a long time. So will Beck, I think. But I think most people on the music scene right now, even a lot of people that are really big names, won't be around. They'll be completely forgotten. 'Cause there's just no substance to their work."

For all his laid-back demeanor, Petty can be a very determined man. Early in his career, he fought tough legal battles with a record label that wanted to overcharge his fans and an ad agency that wanted to use his music to sell tires. He has repeatedly gone to the wall for political causes like Greenpeace, Amnesty International and nuclear disarmament. Petty seems bent on demonstrating that even rock starts can maintain a modicum of dignity. So far, he's done a pretty good job.

"If I was in this for money I would do a lot more things than I do," he says with a laugh. "I don't work very much. I certainly don't promote myself very much. I've passed on a lot of things that are worth a lot of money out there, because they're disgusting to me. And I never have surrounded myself with very much posse. I've seen artists go really wrong by having a lot of people around that keep the myth inflated. I've tried to stay with people who treat me fairly normally. It's really a drag not to be treated normally. I guess there's people who love that and really come to life in those kinds of situations. I don't. I shrink from it. It makes me uncomfortable. I mean, I'm really glad for all the success I've had. I think I would have been very disappointed if it didn't happen and thought 'Shit, I shoulda been famous.' But it really is a double edged sword."

Tom Petty's D.I.D.s

1. Good Vibrations: Thirty Years of the Beach Boys (Capitol, boxed set)

2. The Byrds (Columbia/Legacy, boxed set)

3. Greatest Hits—The Searchers (Rhino)

4. Rainin' in my Heart—Slim Harpo (Hip-O)

5. The Chess Box—Howlin' Wolf (Chess/MCA)

6. Elvis: The King of Rock 'N' Roll—the Complete '50s Masters—Elvis Presley (RCA)

7. Grevious Angel—Gram Parsons (Reprise)

8. Greatest Hits—Wilson Pickett (Rhino/Atlantic)

9. $1,000,000 Worth of Twang—Duane Eddy (Jamie, out of print)

10. A Date With the Everly Brothers (Warner Brothers, out of print)